|

| Singer-songwriter Katy Carr |

You can watch my National Army Museum lecture here: Clare Mulley talking about Krystyna Skarbek at the National Army Museum

Over lunch in the pub afterwards with our mutual friend, Paweł Komorowski, who is a distant cousin of Krystyna Skarbek, I began to learn what made Katy tick. Raised in Nottingham, Katy’s East Midlands accent belies her knowledge and passion for Poland, her mother’s country. This is a woman with a mission to communicate not just the culture and history of Poland, but the individual, and very personal stories, that compose and reflect the nation’s character.

Katy has released four indie-folk music albums, the last of which, the hauntingly brilliant Paszport, was produced in Poland and Britain in 2012. Described as ‘an epic, poetic journey through her past and that of her mother’s nation’, Paszport is dedicated to the Polish experience in the Second World War. Its sixteen songs explore the themes of love and loss, patriotism and resistance, hope and struggle through the prism of Poland’s modern history.

|

| Paszport album cover |

Watch the video here: Katy Carr, 'Mala Little Flower'

The song of Katy’s that I find most moving, however, is ‘Kommander’s Car’, which tells the story of Kazik Piechowski. Kazik was imprisoned by the Nazis for being a Polish Boy Scout at the start of the war and sent on the second transport to Auschwitz in June 1940. It would be two years to the day that Kazik and three fellow political prisoners would realize a plan to steal SS uniforms and drive out of the camp in the car belonging to its infamous commandant, Rudolf Höss. The song, beautifully illustrated here by South African born artist and illustrator Galen Wainwright, manages to convey the emotional truths as well as the factual story of Kazik and his friends’ bid for freedom.

Watch the video here: Katy Carr, 'Kommander's Car'

|

| Two stills from the music video for 'Commander's Car' |

Katy and Kazik’s meeting was documented by British film-maker Hannah Lovell in a short film: Kazik and the Kommander's Car short documentary

|

| Kazik and Katy at a memorial in his local Gdansk park |

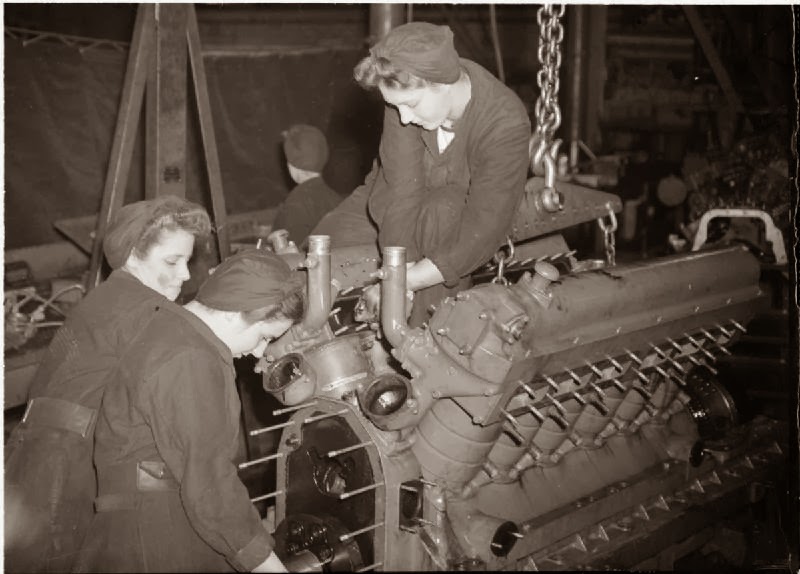

‘Kazik is my inspiration’, Katy told me earnestly, ‘meeting him changed my life’. This is not just some flip patter. Kazik not only inspired Katy to learn more about her Polish roots, he showed her the importance of memory and reaching out to share stories. Kazik has written two books and many articles about his experiences, inspired by the words of the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, ‘You did not survive simply to live, you have little time left, you must give the world the truth’. Katy now also tours schools and local community groups to bring Kazik’s story to new audiences, and to foster stronger relations with local Polish communities across Britain. It is work that has earned her the prestigious Polish Daily Award for Culture as part of their ‘People of the Year’ awards in 2013.

Last year, when my biography of Krystyna Skarbek was published in Poland, Katy and I flew over to Warsaw together, where Katy is something of a star! Paweł came with us too, to generously help promote the book and to toast Krystyna in her homeland. The launch was held at the wonderful Warsaw Uprising Museum, where Katy has performed in the past with her band, The Aviators. However, for me the night before was just as special. Paweł’s wonderful aunt Joanna had invited us over for dinner to meet family and friends including his mother, Babcia. After some fine barszcz czerwony (Polish borscht) and far too much good Polish liquor, Katy got out her ukulele and treated us all to some traditional songs like ‘Hej Sokoły’ - in which you can hear my faintly ludicrous ‘Hej’s’ towards the end! A camera, balanced on a wineglass, recorded the lot: Katy and Babcia Sing 'Hej Sokoly'

|

| Katy singing with Babcia |

There is a lot of talk about immigration at the moment, and this month Polish Foreign Minister, Radek Sikorski, who also came to the Warsaw launch of the Polish edition of my book, blogged that ‘if Britain gets our taxpayers, shouldn't it also pay their benefits?’ I certainly believe that Britain is all the richer, in every sense, for remembering, celebrating and building on our historic connection with Poland during the Second World War. With singer-songwriters such as Katy Carr, I hope that another generation will hear these stories.

I am absolutely delighted to announce that Katy is now working on a song about Krystyna Skarbek for her new album, Polonia. Being released this September, Polonia will mark the 75th anniversary of the start of the Second World War, and the beginning of Poland’s long loss of independence which Krystyna and the Polish Free Forces fought so hard to regain.

|

| Me, with Katy holding The Spy Who Loved |

.jpeg)