Lady Bracknell said it, in Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. "Ignorance, " she pronounced "is a delicate exotic fruit. Touch it, and the bloom is gone."

I am aware that many writers on this blog are immensely knowledgeable about different periods of history and that my studies haven't taken me nearly as deep as they ought to have done, but I enjoy contributing as an interested amateur. My understanding of the history of the Netherlands comes from reading, a long time ago, Simon Schama's excellent book, An Embarrassment of Riches. I have also, of course, read Tracy Chevalier's lovely The Girl with the Pearl Earring and most recently, Jessie Burton's The Miniaturist. Through these books, and of course, even earlier through the Diary of Anne Frank which I read as a teenager, I had an affectionate regard for the Netherlands in general and Amsterdam in particular.

I've just come back from four days in that city and I'm in love. It's a marvellous place, as anyone who's been there knows, and on the basis of this very short visit, I'd like to write about two things. The second is ART (and again, I have only general and not specialised knowledge of this) and the Oude Kerk.

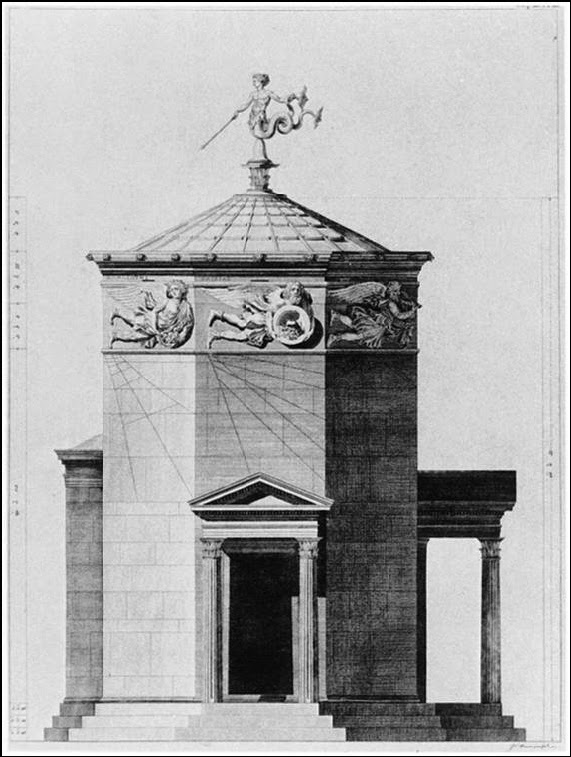

This place is the oldest building in the city. It used to be a Catholic church and then after the Reformation, it became a Calvinist one. My companion, the illustrator Helen Craig particularly wanted to see it because she'd visited it years before and was impressed. So we set out on foot, from very near the Anne Frank house. We walked and walked. Tourist arrows showed us the way, but we did find ourselves going back and round and about and in the end, it took us a long time to find the Oude Kerk even though it is enormous and imposing .We came upon it after asking for directions several times. This is apparently normal. The delightful guide begins: "It may have taken a while to find it, but you've made it. Amsterdams's Oude Kerk is one of the city's best kept secrets."

There was an organ playing when we were there. Someone was rehearsing for a concert. The high pale columns support a vaulted roof. Saskia Rembrandt is buried here. Rembrandt and his family worshipped here. Nowadays it is a space for cultural events of every kind. We walked round an exhibition of photographs and marvelled at images from all over the world celebrating Lesbian Gay and Transgender life. Everything was calm and beautiful and still very church-like. The Oude Kerk has changed through the centuries. In the Middle Ages, it was the busy centre of a growing town. In the Golden Age (17th Century) wealthy trade guilds supported the church and it became a hub for commerce and trade. Today, (and I found this very heartening and somehow moving) it's in the Red Light district. On our way there, on our long walk, we saw pretty young women in bras and panties (they were too lacy and colourful to be 'knickers' ) smiling in the windows of houses where some of the red curtains were drawn shut. These were the sex workers, and it seemed to me that their work was being as respected as anyone else's work, and that the people who passed their windows who were not interested in a sexual transaction were friendly and accepting. A business that could have been sleazy and unpleasant was rendered ordinary and less threatening than it could have been. At no time did Helen and I feel in the least uncomfortable. The women smiled at us as we went by and some even waved. I suppose they are used to the curious glance of strangers, but from the passers-by, I saw neither disapproval or embarrassment on public display.

There are beautiful stained glass windows in the Oude Kerk but the one that I liked was a kind of stained glass collage of bits and pieces that were salvaged when they were restoring the ancient windows.

Next, a haunting collection of lovely dresses in the Rijksmuseum which also incidentally has the best tomato soup I've ever had.

I will be going back. And meanwhile I will plant the tulip bulbs I bought in the Tulip Museum and wait for them to bring to my garden next spring a serene and harmonious kind of beauty which I think of as particularly Dutch.

I am aware that many writers on this blog are immensely knowledgeable about different periods of history and that my studies haven't taken me nearly as deep as they ought to have done, but I enjoy contributing as an interested amateur. My understanding of the history of the Netherlands comes from reading, a long time ago, Simon Schama's excellent book, An Embarrassment of Riches. I have also, of course, read Tracy Chevalier's lovely The Girl with the Pearl Earring and most recently, Jessie Burton's The Miniaturist. Through these books, and of course, even earlier through the Diary of Anne Frank which I read as a teenager, I had an affectionate regard for the Netherlands in general and Amsterdam in particular.

I've just come back from four days in that city and I'm in love. It's a marvellous place, as anyone who's been there knows, and on the basis of this very short visit, I'd like to write about two things. The second is ART (and again, I have only general and not specialised knowledge of this) and the Oude Kerk.

This place is the oldest building in the city. It used to be a Catholic church and then after the Reformation, it became a Calvinist one. My companion, the illustrator Helen Craig particularly wanted to see it because she'd visited it years before and was impressed. So we set out on foot, from very near the Anne Frank house. We walked and walked. Tourist arrows showed us the way, but we did find ourselves going back and round and about and in the end, it took us a long time to find the Oude Kerk even though it is enormous and imposing .We came upon it after asking for directions several times. This is apparently normal. The delightful guide begins: "It may have taken a while to find it, but you've made it. Amsterdams's Oude Kerk is one of the city's best kept secrets."

There was an organ playing when we were there. Someone was rehearsing for a concert. The high pale columns support a vaulted roof. Saskia Rembrandt is buried here. Rembrandt and his family worshipped here. Nowadays it is a space for cultural events of every kind. We walked round an exhibition of photographs and marvelled at images from all over the world celebrating Lesbian Gay and Transgender life. Everything was calm and beautiful and still very church-like. The Oude Kerk has changed through the centuries. In the Middle Ages, it was the busy centre of a growing town. In the Golden Age (17th Century) wealthy trade guilds supported the church and it became a hub for commerce and trade. Today, (and I found this very heartening and somehow moving) it's in the Red Light district. On our way there, on our long walk, we saw pretty young women in bras and panties (they were too lacy and colourful to be 'knickers' ) smiling in the windows of houses where some of the red curtains were drawn shut. These were the sex workers, and it seemed to me that their work was being as respected as anyone else's work, and that the people who passed their windows who were not interested in a sexual transaction were friendly and accepting. A business that could have been sleazy and unpleasant was rendered ordinary and less threatening than it could have been. At no time did Helen and I feel in the least uncomfortable. The women smiled at us as we went by and some even waved. I suppose they are used to the curious glance of strangers, but from the passers-by, I saw neither disapproval or embarrassment on public display.

There are beautiful stained glass windows in the Oude Kerk but the one that I liked was a kind of stained glass collage of bits and pieces that were salvaged when they were restoring the ancient windows.

And I loved the modern tapestry of the seat cushions, done in shades of pale grey and sage green in a kind of willow pattern.

I can't resist saying an ignorant word about the Dutch art that I saw. I came away full of admiration, not only for Vermeer (whose Girl with the Pearl Earring is as beautiful as I expected but almost eclipsed, even so, by the transcendent View of Delft on the opposite wall) and Rembrandt, but also for a whole raft of others, whose names are daunting but who are well worth investigating. Artists like van der Velde, Mignon, de Heem, and van Ruisdael. It seemed to me that they were portraying a world that was basically a good and respectable one; a world based on trade, and farming, and flowers and good governance. Yes, Holland was an imperial power and doubtless that history must have its own share of darkness, but what we mostly see is a place where order and serenity were valued. Of course, death and murder are part of every society, but here it seems the main impulse was towards the light. What is depicted is a place where everyone, whoever they were, had a right to a good life. We associate Holland with tulips and cheese and that cliché says something true about the country: wholesomeness and beauty and a kind of sanity which we only appreciate when we consider other kinds of societies, past and present.

I'm going to finish with a little picture show of some of the things I like best, including, in the Mauritshuis café the best ever Hazelnut Meringue in the whole world and a live flower arrangement in the tradition of those glorious flower paintings of the 17th century.

This is the cake....

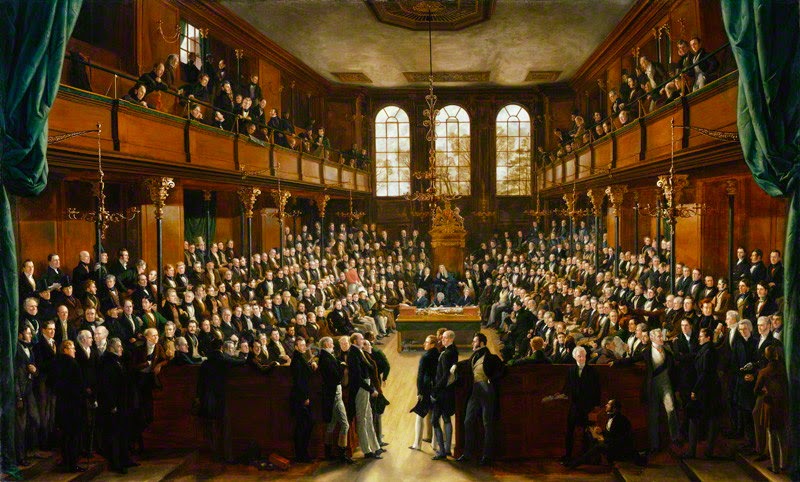

This is from a series of battle scenes by van de Velde, in the Rijksmuseum, done in pen and black ink on canvas. They were stunning.

And here is that flower arrangement.

I will be going back. And meanwhile I will plant the tulip bulbs I bought in the Tulip Museum and wait for them to bring to my garden next spring a serene and harmonious kind of beauty which I think of as particularly Dutch.

.jpg)