For centuries, many noble women in Europe were forced into nunneries by their families either to safeguard their virtue until they could be married off, or to protect family lands by preventing them from marrying and splitting estates. Some women made the best of it, wearing silk gowns under their habits, and spending their days hawking, hunting, dancing and generally enjoying themselves in convents where abbesses would turn a blind eye, and money could buy any kind of pleasure or indulgence. Others found freedom within convents to make serious studies of the arts and sciences, write books, or practise medicine, liberated from the tedious obligations of marriage. But there were some women who refused to settle down quietly behind the cloister walls.

For centuries, many noble women in Europe were forced into nunneries by their families either to safeguard their virtue until they could be married off, or to protect family lands by preventing them from marrying and splitting estates. Some women made the best of it, wearing silk gowns under their habits, and spending their days hawking, hunting, dancing and generally enjoying themselves in convents where abbesses would turn a blind eye, and money could buy any kind of pleasure or indulgence. Others found freedom within convents to make serious studies of the arts and sciences, write books, or practise medicine, liberated from the tedious obligations of marriage. But there were some women who refused to settle down quietly behind the cloister walls.This was the case with two of the nuns of the Sainte-Croix (Holy Cross) in Poitiers in 6th century. The Frankish Princess Clotild, was the child of King Charibert of the Merovingian dynasty and his concubine, a wool-carder’s daughter. Clotild’s cousin, Princess Basina, daughter of King Chilperic, had also been sent to the nunnery, arriving at the tender age of seven, after an assassination attempt on her family. But by then Basina had already been raped by soldiers and had lost her lands too, so she had plenty of cause for anger.

|

| King Chilperic and his queen |

The princesses’ resentment of their lot came to a head early in 589 when they declared that they would no longer put up with the treatment they were receiving from their Abbess, Leubovera, who wasn’t showing them the royal respect they were due. They persuaded 40 fellow nuns to join in them in their rebellion and marched out of the convent, refusing to return until the abbess was expelled. Several bishops to whom they appealed refused to do anything, but finally a female relative of King Guntrum, Clotild’s uncle, promised to ensure a commission would be sent to Poitiers to look into the matter.

But the commissioners showed no sign of hurrying, so the nuns, now back at Poitiers, sought sanctuary at the church of St Hilary from where they recruited a small army of cutthroats and outlaws to defend them, including a notorious murderer Childeric, the Saxon. By the time the commission consisting of four bishops, deacons and clerics arrived, the Church of St Hilary had become a fortress for the nuns and their outlaw gang who were using it as a base to attack the abbess. When the outraged bishops came to the church to excommunicate the rebellious nuns, their whole party was attacked and the clerics, including the bishops, staggered from the church covered in blood and bruises.

Far from being repentant, Clotild urged her gang of mercenaries to seize all the convent’s lands and beat up any who tried to resist. She was only prevented from attacking the main building of the convent by the terrible winter weather which drove many of the nuns to seek shelter in other convents or homes. Clotild and Basina took no notice of the censure of their royal uncles and by Easter 590 were ready to attack the convent itself with the intention of dragging the abbess out, even threatening to throw her from the roof.

Abbess Leubovera, crippled by gout, took shelter in the oratory along with a precious relic of the Holy Cross, but the outlaws broke in during the night and she was only saved from being hacked to death with a sword, by another outlaw who presumably had some qualms about murdering an abbess in front of the relic of the true cross. In the dark and confusion, the Provost Justina, niece of Bishop Gregory, was seized in mistake for the abbess and carried off, but as soon as they realised their error, she was returned to the convent and Leubovera was captured and held prisoner in Basina’s chamber near St Hilary while the convent was looted.

Bishop Maroveus of Poitiers ordered the townspeople to break into the house and release the abbess, but Clotild coolly handpicked a group of men giving them orders to kill the abbess at once should there be any attempt at rescue. In spite of this, a royal envoy managed to snatch the abbess back, but that only led to more violence in which men were slaughtered in the holiest places in the abbey including the shrine of the Holy Cross.

Basina quarrelled with her cousin and made her own peace with the abbess, but this sparked further hostilities between Basina’s supporters and Clotild’s. According to the chronicler of the time, not a week went by without a new murder. Finally, it took the king’s men led by Count Macco to put down the rebellion, slaughtering many of the mercenaries hired by the nuns, while the rest fled back into the forest.

|

| A rather romantic image of the excommunication of a later Frankish king, Robert II (972-1031), known Robert the Pious, who invoked the Pope's wrath by marrying his 1st cousin. |

In any case, thanks to intervention of King Childebert II, the Church Council was persuaded to restore them to grace a few months later. Perhaps the King intervened because he knew if the sweet little princesses were not readmitted to the Church he’d have no chance of banishing them safely to a convent again and he didn’t want to risk those two running around his kingdom uncloistered.

|

| Radegund who founded Saint-Croix abbey |

Basina did return to the life of a nun in Saint-Croix in Poitiers and, so the chroniclers say, lived there ‘in obedience’ for the rest of her life. But Clotild had no intention of meekly returning to a nunnery. Despite being illegitimate, she persuaded the king's mother, the infamous Queen Brunhilda, to grant her lands which she ruled until her death.

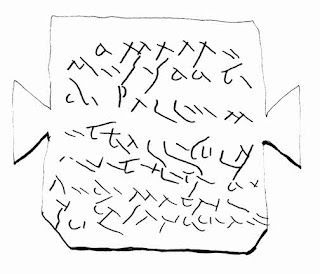

Incidentally, the abbey of Saint-Croix had been founded by an earlier Frankish Princess, Radegund, around 560, when she fled her murderous husband. The rule she established meant that the nuns were very strictly enclosed, but allowed many hours to read and write. Radegund herself wrote Latin poems which she gave to the poet Venantius Fortunatus and to the bishop and historian, Gregory of Tours, who both became great friends. So she was one noblewoman who was grateful for the peace of her seclusion.

Incidentally, the abbey of Saint-Croix had been founded by an earlier Frankish Princess, Radegund, around 560, when she fled her murderous husband. The rule she established meant that the nuns were very strictly enclosed, but allowed many hours to read and write. Radegund herself wrote Latin poems which she gave to the poet Venantius Fortunatus and to the bishop and historian, Gregory of Tours, who both became great friends. So she was one noblewoman who was grateful for the peace of her seclusion.