|

| Dame Henrietta Barnett |

Henrietta Barnett was one of those formidable late Victorian/Edwardian dames who set out to change the world. Along with her husband, she set up a 'settlement' in Whitechapel in the East End of London to help and educate the poorest of the poor, it's still there -Toynbee Hall - and Canon Barnett has a primary school named after him nearby.

Henrietta herself was interested in the burgeoning new towns movement. She saw an opportunity to build a model suburb, one where rich and poor would live together in a semi rural idyll with public woods, low density housing and clean air. She was also big - very big - on the education of girls. This would be a place to build a new society, far from the filth of the city, up high on a hill outside London. It was born out of a mixture of the idealism of late Victorian England, Arts and Crafts and back to the land, an idyll of space for all according to their need.

So Hampstead Garden Suburb was born, a place with a central square laid out by architect de jour Lutyens, with education at its heart. There was an adult education Institute (Orwellianly named 'The Institute') and the school, named after the Dame herself. all roads were to be tree lined, and there were to be no church bells rung. She even vetoed the building of the Underground Line, no tube stations here thank you! Also what's noticeable is that even in this brave new world, the houses farthest from the Central Square and the Heath are smaller, meaner. This was a carefully zoned kind of socialism after all.

I don't know what the Dame would make of it today. The Institute has moved out of The Suburb (that's what it's called, The Suburb, as if there isn't any other) and only the very very (very) rich live there these days. It's cut in two by the North Circular road, so I doubt the air is as clean as it was a hundred years ago...

What has this got to do with John Lennon? I am getting to this....

Close your eyes. Let the years fall away.

|

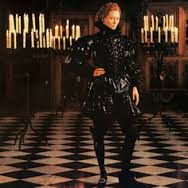

| Henrietta Barnett School |

Oh. And another.

This was a mirror to my school life in which everything went downhill very slowly fading out like John and Yoko. My school, I was sure, was the most boring, most turgid, and the most uninspiring place in the whole universe.

It was designed to offer free education to girls who at 11 managed to jump through the hoops of the 11 plus. It never had the glamour or sass of it's near neighbour Camden Girls. HBS girls were always well behaved and useful members of society; Opticians, Estate Agents, Dentists and Doctors*. It might be a school parents fight to get their girls into - it's free! it's socially exclusive! it has great exam results! There is no scope for lunchtime excitement as the school is miles from ANYWHERE! (Dame H banning the tube station totally worked).

So the Grey Cat? Well this year isn't easy at the best of times, everyone posting happy Christmas pics when for a lot of us it hasn't been. People making brave and bold resolutions and brave and bold new years.

I have been lucky never to have been visited by the Black Dog of depression, but many around me have. All of us know what it's like to feel empty with pain or to feel so sad and terrified of life that you can't eat or breathe.

One thing I wish I could have told myself as I lay on my back on the parquet in my navy leotard is that it gets better - as well as worse.

I think children are sold a pup. Life isn't the mirror to school, progressing up one class after another, come what may. That's completely unnatural. Things go up and down. There will be bright spots and utter lows. Both are a kind of illusion. Keep going. The Grey Cat - unlike the dog which needs proper help - will pad past on silent paws.

I am a fan of contentment. Of the middle road. Of the just about alright. Of the 'it could always be worse'.

But of course I would be lying if I didn't harbour secret hope - why on earth write otherwise?

Here's hoping for all of us that the year brings contentment and good health.

Happy New Year!!

The Curious Tale of the Lady Caraboo is out now, published by Corgi.