↧

"500 Years of Female Portraits in Western Art" - Joan Lennon

↧

In search of Babylon's dragons - Katherine Roberts

Over the past month, I've been painting the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (for the e-covers of my Seven Fabulous Wonders series, but that's just an excuse for some fun). In doing so, I unearthed one of the strangest creatures in history... the Babylonian "dragon", shown here on the Ishtar Gate, constructed around 575BC by King Nebuchadnezzar II:

The two children are playing a game called Twenty Squares - sometimes called the Royal Game of Ur - on a simple board scratched into the pavement, just as the guards of Babylon might have done to pass the long hours of their shift. The walls of Babylon are blue-glazed brick with gold bricks for decoration, and on the gate you can see two types of creature that are extinct today - aurochs and sirrush. The dragon perched on the top left is obviously my fantasy side rearing its ugly horned head... but in case you think I've invented the creatures entirely, here is a reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, which uses the original bricks found at Babylon:

There also is/was (I believe it suffered in the recent war) a replica of the Ishtar Gate in Iraq, too:

You may scoff at the idea of flying, fire-breathing dragons straight out of a fantasy novel. But auroch skeletons have been found, and the bulls shown on the Ishtar Gate are now accepted as an extinct creature that once roamed the banks of the Euphrates. So why not the other creature... the dragon?

Take a closer look:

You'll see it has a single straight horn in the middle of its forehead and a curly horn (or ears?) at the back. It also seems to have scales and a thin lizard-like body, much like dragons that could possibly be descended from dinosaurs. It has bird-like claws on its hind legs, but those paws on its forelegs look more like a lion's, and it seems to have hairy (or feathery?) legs. Significantly, it has no wings. Some people think it might actually be a unicorn - another creature that has made the leap into legend. The Babylonian texts call it a 'sirrush' or 'mushussu'/'mushkuku' (depending on how you interpret the cuneiform), and it is shown on cylinder seals of the period being led by a halter, where it appears to be about the size of a large dog.

So what do you think? Did this creature exist? Have we just not found its skeleton yet, or maybe mistaken its bones for those of other creatures - lions/birds/lizards? In my story, the sirrush sheds its skin like a snake and emerges with a pair of beautiful wings, explaining how it might have flown away into legend.

It's not too big a leap of imagination (at least not for me!) to believe a few remaining dragons might have been kept alive in a royal garden or park such as the second Wonder of the Ancient World, the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Perhaps this vanished Wonder was actually an exotic zoo, as imagined by my Japanese publisher?

Whether Babylonian dragons existed or not, they are certainly alive and kicking in my book. And now they have entered the 21st century on the ecover, which after some digital wizardry looks like this:

More Seven Wonders paintings at Reclusive Muse.

www.katherineroberts.co.uk

|

| The Ishtar Gate... with a Babylonian dragon? |

The two children are playing a game called Twenty Squares - sometimes called the Royal Game of Ur - on a simple board scratched into the pavement, just as the guards of Babylon might have done to pass the long hours of their shift. The walls of Babylon are blue-glazed brick with gold bricks for decoration, and on the gate you can see two types of creature that are extinct today - aurochs and sirrush. The dragon perched on the top left is obviously my fantasy side rearing its ugly horned head... but in case you think I've invented the creatures entirely, here is a reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, which uses the original bricks found at Babylon:

|

| Ishtar Gate of Babylon - reconstruction, Berlin |

There also is/was (I believe it suffered in the recent war) a replica of the Ishtar Gate in Iraq, too:

|

| Replica of the Ishtar Gate in Iraq |

You may scoff at the idea of flying, fire-breathing dragons straight out of a fantasy novel. But auroch skeletons have been found, and the bulls shown on the Ishtar Gate are now accepted as an extinct creature that once roamed the banks of the Euphrates. So why not the other creature... the dragon?

Take a closer look:

|

| sirrush (from Koldewey's The Excavations at Babylon, 1914) |

You'll see it has a single straight horn in the middle of its forehead and a curly horn (or ears?) at the back. It also seems to have scales and a thin lizard-like body, much like dragons that could possibly be descended from dinosaurs. It has bird-like claws on its hind legs, but those paws on its forelegs look more like a lion's, and it seems to have hairy (or feathery?) legs. Significantly, it has no wings. Some people think it might actually be a unicorn - another creature that has made the leap into legend. The Babylonian texts call it a 'sirrush' or 'mushussu'/'mushkuku' (depending on how you interpret the cuneiform), and it is shown on cylinder seals of the period being led by a halter, where it appears to be about the size of a large dog.

So what do you think? Did this creature exist? Have we just not found its skeleton yet, or maybe mistaken its bones for those of other creatures - lions/birds/lizards? In my story, the sirrush sheds its skin like a snake and emerges with a pair of beautiful wings, explaining how it might have flown away into legend.

It's not too big a leap of imagination (at least not for me!) to believe a few remaining dragons might have been kept alive in a royal garden or park such as the second Wonder of the Ancient World, the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Perhaps this vanished Wonder was actually an exotic zoo, as imagined by my Japanese publisher?

|

| Japanese edition of The Babylon Game |

Whether Babylonian dragons existed or not, they are certainly alive and kicking in my book. And now they have entered the 21st century on the ecover, which after some digital wizardry looks like this:

***

Katherine Roberts' Seven Fabulous Wonders series is re-available as ebooks for Kindle and epub formats, or you can download the complete collection of seven books for half the combined list price as the Seven Fabulous Wonders Omnibus.

More Seven Wonders paintings at Reclusive Muse.

www.katherineroberts.co.uk

↧

↧

GREENWAY by Adèle Geras

In the middle of April, I spent five days at Greenway. This is the country home of Agatha Christie, on the banks of the River Dart, just across the water from the pretty village of Dittisham.

Greenway House was built in 1792 but Agatha bought the property in 1938 and spent many holidays here. The house is large and square and stuccoed in cream. It looks over lawns and trees and a magnificent array of magnolias, rhododendrons and camellias. The sun shone for the whole time we were there and the shrubs were at their very best. Since 2009, Greenway has been a National Trust property and the old servants' quarters have been turned into an apartment that can sleep 10 people. It's comfortable and also old-fashioned....you feel that Agatha herself might easily come walking into the lounge or sit at the dressing table in one of the bedrooms. In the bookshelf in my room, for instance, I found a Gwen Raverat's Period Piece with this dedication:

I read and loved Agatha Christie back in the 1950s and early 60s, but now have a personal connection with the Queen of Crime. My daughter, Sophie Hannah, has written a new Hercule Poirot novel and has been obsessed with all things Christie for eighteen months or so. The name of this novel is embargoed till tonight but I will put it up in a comment below this post so if you want to see what it is, come and have a look tomorrow.

Here is one of the paths leading down to the river. Agatha was very keen on gardening and there are gardening books on many bookshelves. The planting is inspired. Periwinkles, bluebells, tulips, fuchsia and banks and banks of azaleas make a walk around the property a real pleasure.

This typewriter was on the windowsill at the end of the passage in the guest apartment. I suppose that means it's not actually the one Agatha wrote on...that would have been moved to the House itself. Still, it's an old machine and it's here so I like to think she must have written at least a letter or two on it. It is, whoever used it, a beautiful object, I think.

The first thing that strikes you as you walk around the house is what a collector Agatha was. Here are some snuffboxes, but she also assembled a great deal of crockery, ornaments, books, pictures, and assorted pieces of archaeological pottery, connected to the work of her husband, Max Mallowan. She used to accompany him to his archaeological sites and work on her books while he was overseeing the digs.

This doll ( above) has, like a great many dolls, a touch of the sinister about her. Below is the portrait of Agatha when she was four. I love it because the artist has captured exactly a kind of sulky boredom that's not often depicted by artists.

And here is the top of the grand piano, full of family photos.

There are several dressers in the house. On this one, alongside the crockery, is a skull, which struck me as appropriate.

A great many books are displayed both in the house and in the apartment. You can see scrapbooks and letters and on various tables there are envelopes addressed to the author, looking as though they've just been delivered. I wanted to take photos of these but for some reason my camera decided to malfunction just at that moment.

Here are some of the toys arranged on a sofa. I love the mad look on the eyes of the doll on the left. And that teddy has been loved to bits by someone, maybe even Agatha herself.

Finally, wisteria, growing beside the greenhouse in the Walled Garden. The greenhouse is full of tropical plants and cacti. There are espaliered trees, and a herb garden with everything in it: sage, marjoram, lemon balm, dill, orange-scented thyme, rosemary, and bay.

Agatha Christie called Greenway "The loveliest place in the world." She had travelled widely but Greenway's tranquil atmosphere, and the thousand shades of green that she could see from the windows of her house made this place into the best kind of home. Her benevolent and inspiring presence is everywhere here. If you find yourself in the area, it's a wonderful place to visit. I loved my time there.

↧

'Toad, Long Crippler and Snake' by Karen Maitland

|

| Leechwells at Totnes, Devon |

Recently a triangular immersion pool was discovered behind one of the walls. This, together with the three springs and three branches of the path leading to the wells, made a number which was important both to the medieval Christian – three times the trinity – but also to those who still followed the elder faiths, for nine was the number of completeness or wholeness. So what must have been an ancient pre-Christian site, easily became adopted as site of Christian pilgrimage.

|

| Offerings are still left at the leechwells today |

For me one of the most fascinating aspects of this magical place are the ancient names given to the three springs which are in the photo above, from left to right, ‘Toad’, ‘Long Crippler’ and ‘Snake’. They sound like the ingredients of a witch’s cauldron in Macbeth. By tradition the spring known as ‘toad’ was supposed to cure skin diseases, ‘long crippler’ which is an ancient name for a slowworm, cured eye problems and ‘snake’ healed snake bites and melancholia. But why would the names of three creatures believed in the Middle Ages to be poisonous come to be associated with healing wells?

|

| Witch feeding her her familiars or bids in the form of toads. |

|

| A slowworm otherwise known as a blindworm. |

Snake– that is more obscure. Although the Rod of Asclepius, the serpent-entwined staff, has been adopted as a medical symbol, this cannot have been the association here. We only have one poisonous snake in Britain and today few people are bitten, so I can’t imagine many people in Totnes today would have cause to rush to the spring for treatment. Yet, in the middle ages and earlier there are a large number of legends of plagues of snakes infesting towns generally driven out by saints such as St Hilda, St Keyna and St Birinus. Birinus when dying from a adder bite, declared that anyone who stayed within the sound of the church bells at Dorchester would henceforth be protected from snake bites. The Tenor or heaviest bell at Dorchester cathedral, cast in 1380, is inscribed with the prayer ‘Protege birine quos convoco tu sine fine. Raf Rastwold’ – ‘Birinus, protect for ever those whom I summon. Ralph Rastwold. And the superstition says that vipers will slither away at the sound of the bell.

|

| Witches adding a snake and other creatures. |

No snake or adder ere can dwell.’

Were there plagues of snakes in the middle ages? Certainly more people worked on the land then, therefore there may have been more bites. But a more probable explanation was that the adder or viper was associated with evil and the devil, so was thought to be a creature of ill-omen bringing bring bad luck. In Christian times, a snake spring might have been used not so much to cure actual bites, but to break of run of bad luck or misfortune and to ward off evil.

So if you are visiting Totnes – you might want to take a bottle with you to fill at the snake spring just in case.

↧

Writing Historical Fiction for Dyslexic Readers

by Caroline Lawrence

In 2013 I was approached by Barrington Stoke, a publisher who specialises in fiction for dyslexic readers. They ask established writers to write books in their particular field of expertise for dyslexic and reluctant readers. I was excited when they asked if I would be willing to write a book of around ten thousand words specifically geared to teenage boys.

I immediately thought of the Aeneid, one of my favourite works of Classical literature. Nobody does gory battle scenes better than Virgil. One of the best stand-alone stories from the Aeneid, with plenty of gore, is the story of the doomed night raid by Nisus and Euryalus. It’s visceral, exciting and almost cinematic (like much of Virgil) in its descriptions.

I wanted a killer first paragraph to hook reluctant teen readers. Inspired by the classic openings of two films, Sunset Boulevard and American Beauty, I opened my story with a narrator telling what it feels like to die.

I was young when they killed me. Just a teenager.

They say death on the battlefield wins you true glory.

They say when someone stabs you it doesn’t hurt.

They say it feels like a fist punching you.

That you hardly even notice it in the excitement of the battle.

They are wrong.

You do notice when someone plunges a sword into your body.

It doesn’t feel like a fist punching you. It feels like a heavy, iron, double-edged sword. The blade pierces your skin, parts your muscles, scrapes your bones and pops your organs.

It burns cold. Freezes hot. Then makes you want to puke.

It does not feel glorious.

It hurts like Hades.

Which is where I am bound.

When you write for Barrington Stoke there are two stages of editing. The first edit is for the story itself – structure, continuity and comprehensibility. The second edit aims to weed out words and phrases that might trip up dyslexic readers. Ruth, my main editor, warned me to avoid participle phrases and complicated sentences from the beginning as these would almost certainly be cut. I tried to keep the syntax as simple as possible and the vocabulary, too. As fans of Hemingway and Robert B. Parker know, you can tell a good story with simple words.

I had just finished the first draft of The Night Raid when I went to a boys’ prep school called Summer Fields in Oxford to do a week as writer in residence. This was my target audience: boys 8-12 years old. I didn’t have time to read long passages during my workshops, but I gave the manuscript to Sophie Palmer, one of the English teachers there. The great thing about Sophie is that she herself is dyslexic and knows all the problems other dyslexic readers might have. Sophie read the first couple of chapters to the boys in her class and they came back with some great comments. My favourite was one boy’s criticism, that it seemed too much like a movie!

Sophie also gave me a checklist of things boys like:

1. a hero they can relate to

2. adventure – straight into action

3. all goes wrong – failure – then all goes right

4. setting the scene

5. creating a sense of foreboding

6. when the reader knows something the main character doesn’t

7. twists and turns

8. a good title and front cover

9. humour

10. quick pace

I took on board some of her suggestions, especially those which entailed changing words the boys didn’t understand.

I also showed an early draft to Llewelyn Morgan, a respected professor of Classics at Oxford and an expert in Virgil. He gave me the thumbs up and so did his son Tom, "aged 10 and a harsh critic".

Writing a version of Virgil with such strict constraints was strangely satisfying. I found my prose tauter and tighter. I found I could write historical fiction without using exotic words. Under my editor’s encouragement, I changed column to pillar, slaughtered to butchered and rations to food.

Unfamiliar words were simplified or explained. Callus became hard patches of skin. Palisade became spiked walls. Eternity became all time.

The specialist-dyslexic editor, Mairi, also made some basic changes, like replacing adjectives with action verbs. Nodded happily became nodded and smiled. I said quickly became My next words came fast. And muttered sourly became muttered sour words, which I much prefer.

I don’t think my retelling has lost anything because of these constraints. In fact I think my writing has become clearer and more accessible. With the fabulous cover Barrington Stoke have produced I have an excellent chance of catching the attention of normally reluctant readers, especially teenage boys. If this target audience finds their interest sparked by a simply-told glimpse into Virgil’s great masterpiece then it will have been well worth the effort.

The Night Raid, Caroline Lawrence's first book for Barrington Stoke, will be launched on Monday 12 May at Summer Fields School in Oxford. You can read a sneak peek HERE.

|

| The Roman poet Virgil |

I immediately thought of the Aeneid, one of my favourite works of Classical literature. Nobody does gory battle scenes better than Virgil. One of the best stand-alone stories from the Aeneid, with plenty of gore, is the story of the doomed night raid by Nisus and Euryalus. It’s visceral, exciting and almost cinematic (like much of Virgil) in its descriptions.

I wanted a killer first paragraph to hook reluctant teen readers. Inspired by the classic openings of two films, Sunset Boulevard and American Beauty, I opened my story with a narrator telling what it feels like to die.

I was young when they killed me. Just a teenager.

They say death on the battlefield wins you true glory.

They say when someone stabs you it doesn’t hurt.

They say it feels like a fist punching you.

That you hardly even notice it in the excitement of the battle.

They are wrong.

You do notice when someone plunges a sword into your body.

It doesn’t feel like a fist punching you. It feels like a heavy, iron, double-edged sword. The blade pierces your skin, parts your muscles, scrapes your bones and pops your organs.

It burns cold. Freezes hot. Then makes you want to puke.

It does not feel glorious.

It hurts like Hades.

Which is where I am bound.

When you write for Barrington Stoke there are two stages of editing. The first edit is for the story itself – structure, continuity and comprehensibility. The second edit aims to weed out words and phrases that might trip up dyslexic readers. Ruth, my main editor, warned me to avoid participle phrases and complicated sentences from the beginning as these would almost certainly be cut. I tried to keep the syntax as simple as possible and the vocabulary, too. As fans of Hemingway and Robert B. Parker know, you can tell a good story with simple words.

I had just finished the first draft of The Night Raid when I went to a boys’ prep school called Summer Fields in Oxford to do a week as writer in residence. This was my target audience: boys 8-12 years old. I didn’t have time to read long passages during my workshops, but I gave the manuscript to Sophie Palmer, one of the English teachers there. The great thing about Sophie is that she herself is dyslexic and knows all the problems other dyslexic readers might have. Sophie read the first couple of chapters to the boys in her class and they came back with some great comments. My favourite was one boy’s criticism, that it seemed too much like a movie!

Sophie also gave me a checklist of things boys like:

1. a hero they can relate to

2. adventure – straight into action

3. all goes wrong – failure – then all goes right

4. setting the scene

5. creating a sense of foreboding

6. when the reader knows something the main character doesn’t

7. twists and turns

8. a good title and front cover

9. humour

10. quick pace

I took on board some of her suggestions, especially those which entailed changing words the boys didn’t understand.

I also showed an early draft to Llewelyn Morgan, a respected professor of Classics at Oxford and an expert in Virgil. He gave me the thumbs up and so did his son Tom, "aged 10 and a harsh critic".

Writing a version of Virgil with such strict constraints was strangely satisfying. I found my prose tauter and tighter. I found I could write historical fiction without using exotic words. Under my editor’s encouragement, I changed column to pillar, slaughtered to butchered and rations to food.

Unfamiliar words were simplified or explained. Callus became hard patches of skin. Palisade became spiked walls. Eternity became all time.

The specialist-dyslexic editor, Mairi, also made some basic changes, like replacing adjectives with action verbs. Nodded happily became nodded and smiled. I said quickly became My next words came fast. And muttered sourly became muttered sour words, which I much prefer.

I don’t think my retelling has lost anything because of these constraints. In fact I think my writing has become clearer and more accessible. With the fabulous cover Barrington Stoke have produced I have an excellent chance of catching the attention of normally reluctant readers, especially teenage boys. If this target audience finds their interest sparked by a simply-told glimpse into Virgil’s great masterpiece then it will have been well worth the effort.

The Night Raid, Caroline Lawrence's first book for Barrington Stoke, will be launched on Monday 12 May at Summer Fields School in Oxford. You can read a sneak peek HERE.

↧

↧

April Competition Winners

The winners of the April competition are:

Liz

Margaret Skea

Gerry McCullough

Please send your land addresses to:

readers@maryhoffman.co.uk

to claim your prizes.

Congratulations!

Liz

Margaret Skea

Gerry McCullough

Please send your land addresses to:

readers@maryhoffman.co.uk

to claim your prizes.

Congratulations!

↧

Hair in all the wrong places – Michelle Lovric

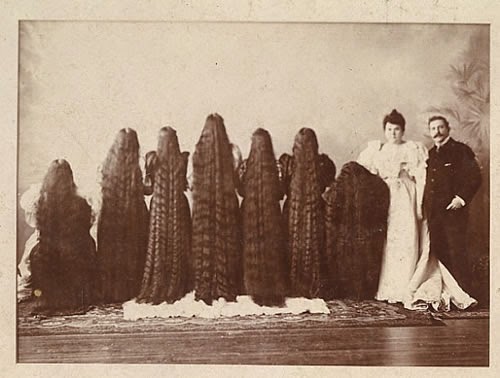

My forthcoming novel, The True & Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters, is about hair.

Long, vigorous yet soft, feminine hair. Hair that flows in rich torrents from seven pretty heads. Hair that can be put to work, making money for men who peddle long-tressed dolls and quack medical products for the scalp.

For The Harristown Sisters is set in the 1860s, the age of arch pseudo-medicine, when human perfectability was for sale in a bottle whose contents could be advertised without any regulation as to truth or safety. A new power-base in the feminine purse, in the mid nineteenth century, shared a cultural vortex with the Pre-Raphaelite painters and the poets who both celebrated and problematized the hair of women as an expression of passionate and unruly desires.

The English Poetry Database, where I first began my researches, teemed with 19th century works featuring ‘hair’, ‘curl’ and ‘tresses’. Browning, Rossetti and their lesser ilk wrote longingly of lying under silky tents of feminine hair, or of being strangled by the fatal tresses of supernatural sirens like Lilith, Adam’s first, wicked wife, who alleged dined on human babies. Above is Monna Vanna, by Dante Gabriele Rossetti and below his Lady Lilith, now at the Delaware Museum (both paintings courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

And the matrons of England and America were encouraged to spend on their hair, on the principle that a husband would remain captivated by his wife’s long-flowing feminine charms while her sensible housekeeping extracted only dry compliments.

It was the age of Edward’s Harlene, Koko for the Hair and most of all the preparations of America’s Seven Sutherland Sisters, who had thirty seven feet of hair between them. They are pictured in one their classic poses below - they performed in circuses and shows where they sold their Scalp Food and Hair Restorer, being living advertisements for the efficacy of these potions. These sisters provided the inspiration for my novel, though I chose to set it in Ireland and Venice, where the Pre-Raphaelites, the earlier artists who inspired them, and the dawn of photography had more cultural resonance in my study of hair.In the course of my research I also explored the problem of hair where hair should not be. In mid-Victorian times, this was personified by Julia Pastrana, the diminutive Mexican ‘Baboon Lady’ who danced the Highland Fling and sang on the stage to the horror and delight of American and British audiences.

Weeds are sometimes described as plants simply growing in the wrong place. Hair that grows abundantly in the prescribed zones is a bio-marker of desirable breeding stock. A hand running through a curl attached the beloved’s head finds only pleasure and sentiment. But when hair appears in the wrong place – such as in our soup – we feel revulsion and a sense of dirtiness.

Julia Pastrana – a gentle soul who spoke three languages and loved sewing – suffered from hypertrichosis. She was furred all over her body, had a beard and a simian visage caused by another rare condition, Gingival hyperplasia.

The treatment of Julia Pastrana taps into two key moral debates of our own time: where does celebrity culture cross over into criminal intrusion and venality at the expense of the prey? And why is the ‘disgusting’ such a viable commodity? Embarrassing bodies, sexual failure, eating disorders: there’s a pornography of body dysfunction paraded on the television screens every night of the week.

A play and a film have been written about Julia Pastrana, and a third is in production. The Ass Ponys recorded a song about her mind, life and marriage, with a refrain ‘He loves me for my own sake’, highly ironic under the circumstances.

It is less than two years since Julia Pastrana’s body finally received a picturesque burial in her native Mexico. As an exercise in empathy, during the writing of The Harristown Sisters, I decided to write a personal essay as Julia Pastrana. People who are monstered rarely have voices. It is the way of dehumanization to render the victim silent. I wanted to give Julia the privilege of looking out of her anathematized body, instead of merely being looked at. I also wondered what she would have thought about her posthumous repatriation to Mexico, and finally concluded that it would find small favour with her.

This part of my research was not published, but it informed a great deal of what I wrote about in The True & Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters.I wonder if others among you find that some of your most interesting work stays off the published page? Examples, please!

This post really ends with that question, but below, as an optional extra, is my personal essay as Julia Pastrana. Michelle Lovric's website

Unless otherwise attributed, the pictures are courtesy of Wellcome Images, which has recently made its wonderful historical collection available for general use.

The True & Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters is published on June 5th by BloomsburyJulia Pastrana

Eighteen thirty-four, I’m born in Mexico, a baboon of a baby, hooded whiteless eyes filled up with lucent brown. My jaw thrusts out like an orange, or a bustle, split by two great slugs of lips snug over double rows of teeth. My forehead slopes steeply back; there’s fur on my feet, and shags and tufts and gouts of hair everywhere, everywhere that hair shouldn’t be.

By three my beard was tied with string. My tribe in Sinaloa de Leyvamumbled things about my mother but they let me live. Ma slapped children when they screamed at the sight of me, but I guessed from her averted eyes and sparing hands that she wished me unborn. I could not crawl back inside her so I grew away from her.

I peaked at four and a half feet, with breasts, beckoning thighs, a supple dancing style, a melodious voice, a tongue for languages, a cool hand for pastry, and a desire to please the men with hair where hair should be.

A pink ribbon round my beard now, tight-laced in a Spanish dress, I was hired as a servant girl to the governor of Sinaloa. My mother’s eyes were opaque as the cart took me away. She did not wave

The governor brought me out after dark to serve port to male guests. One of them, a Mr Rates, watched me with long eyes through the candle flames. Late in the night, he threw a purse across the table.

My billing was ‘The Marvelous Hybrid or Bear Woman’, she of the gorilla’s jaw, ape’s eyes, and hair where hair should not be. The New York papers showed their love: ‘terrifically hideous’, they said I was.

The doctors lifted, inserted, prodded till I cried. Mott from the Medical Society pronounced me ‘the most extraordinary being of the present day’, being the result of my Mexican mother mating with an orang-utan. Proof of her depravity: she’d sold me to the circus. If I mentioned otherwise, Mr Rates told me quietly, he’d skin me for my pelt and stuff me.

‘Then,’ he reflected, ‘you’d be pure profit. No cost in food and board. Remember this.’

The demi-monkey waltzed with soldiers at a military gala, knowing the fellows had been dared, feeling their reluctance through the tense fingers on my back, where my gown crushed the fur almost but not quite flat.

In Boston I was styled ‘the Hybrid Indian: The Misnomered Bear Woman’– by the Horticultural and the Boston History Society. Neither could decide whether ‘animal’ or ‘vegetable’ best described the thing I was.

Mr Rates sold me to J.W. Beach of Cleveland. From him, I came into the possession of one Theodore Lent, my small-eyed darling, my bearded destiny, who, judging me worth the passage, carried me off to London, where they went mad for me and the hair that grew where hair should not be, while I fell deep in love with Lent, and he not at all with me.

How it clamped my heart when my love billed me ‘The Nondescript’. He claimed it meant my marvels surpassed description. It did not. ‘The grotesque’s dancing is like a fairy’s,’ the London papers wrote. ‘The monster sings romances and lilts Highland Flings to perfection.

Charles Darwin wrote of me kindly, but published me in The Variation of Animal and Plants under Domestication.

By now I spoke a lady’s English. My knitting was a credit to me, though my Theodore refused to touch the gaiters I made him. He’d swallow my little suppers with an averted face.

He coached me to tell of twenty marriage proposals turned down: to say that no admirer had yet proved rich enough to catch my glistening eye.

‘There will be someone,’ he promised, ‘There’s always someone with an itch for a thing like you.’

He toured me in Berlin and Leipzig to raise my price. I acted in a play, Der curierte Meyer. A German boy falls in love with a veiled woman. But when he goes offstage, I lift the gauze, convulsing the audience with hilarity at the horror of my baboon face. When my lover sees me unveiled, his cure is instant. I rehearsed with Theodore, till I could take it without flinching.

No rich suitors came to marry me, but other handlers loomed in, offering terms and smiles. Theodore proposed. On our wedding night, he closed his face, the shutters, the curtains and put out the light. He divided me rough and sudden from my girlhood. In the morning, he was gone, and stayed gone for days. I did not allow the stained sheets changed and lay sleepless on my hardened blood, remembering. My heart beat like jungle rain when he appeared again; I cried from joy if his lips curved upwards. His eyes never smiled when they looked on me.

In Vienna he let more doctors pay to do what he had done in the darkest part of me, with sharp cold tools instead of his hard heat and shouted obscenities. He locked me in our rooms by day. In Poland and Moscow, he grew crueller and harder though I stood on tiptoe in everything to please him. He still came to me some nights, roaring on gin. He clapped his hand over my great lips, grasped the bedstead rungs and laboured on me. Afterwards he’d fling himself from me, groaning, to vomit in his chamber pot and strode swearing from the room.

Yet he got a child on me.

No baby ever had such a delightful layette, every item stitched by me. The nursery I had painted all the colours of hope. Of course I wondered what was growing inside me, the little stranger was already beloved. Theo kept away. If I saw his face, it was in profile only.

He did not burn the anonymous letters but left them for me to see. You have mated with a beast. You have stained mankind with bestiality.

The birth tore my narrow hips apart. Worse than pain was the sight of my son who took after me with whiteless eyes, bustle-jaw and hair where hair should not be. I slapped myself so as not to scream at the sight of him. His hours of life were thirty five.

‘Put it in a bucket and throw it in the river,’ Theodore told the maid.

Puerperal sepsis seized me like a serpent, poisoned me, shook me, till I saw Sinaloan ghosts again, the New York stage, Theodore’s face. My widower did not visit my deathbed, sent the photographer instead. He was in deep negotiations to sell our two corpses to Professor Sukolov at the Anatomical Institute in Moscow, and had gone to buy a monkey the height of a two-year-old child. The public, he told the maid, loving horror as they did, would not accommodate a baby, even semi-human, stuffed. ‘Better this,’ he said, wringing the monkey’s neck and kissing the maid’s.

At the sound of his lips on her skin, my hairless soul rose from my corpse. No funeral. Instead, I watched Sukolov dissect the monkey and me side by side on stained slabs. I saw the scalpel separate my skin, cried out soundlessly when he chose a finer blade for the poor small creature. I began to feel for my monkey child a fierce new love.

For six months, the professor hovered over us, extracting, scouring, packing, stitching us to such perfection that we retained our colour and our form. My sawdust-stiffened limbs were mounted in my old dancing pose, hand on hip. A crucifix hid the seam that held my breasts together. Sewn into a short Spanish dress, I was set up in a glass case, my false simian son in a sailor suit on a pedestal in a separate box where I might stare at him as the paying customers did.

News came to Theodore of the great crowds we drew and the great sums made for Sukolov. Our marriage certificate, presented to the American consul, robbed the Russian professor of his hard-won profits. That gaunt February of sixty-two, Theodore shipped us back to England; charged a shilling a look at the ‘Embalmed Nondescript’ and her progeny. Then he hired us out to a travelling museum of curiosities, I, the monster with hair where hair should not be, still topped the bills and filled the tents.

By now Theodore had found a girl near as hairy as myself. He set her up as “Zenora Pastrana”, my sister. He married her as well. The four of us, two living and two dead, toured till Theodore tired – his calculating mind slowed for the first but not the last time to a sick ticking. He rented his first wife and supposed son to a Vienna museum. With my corpse retired, he claimed that Zenora was me. The two repaired to St Petersburg, bought a waxworks. It was there my Theodore, Zenora’s Theodore, the stock exchange’s Theodore went mad. In the asylum, my spirit watched him long days writhing on his bed. It danced my Highland Fling for him, combed the hair where it should be, and touched him till he shrieked. He died insensible or perhaps fully sensible of me for the first time.

In eighty-eight, Zenora left Russia, reclaimed our bodies, toured them. Wooed by a young man, she sold us to an anthropological exhibit in Munich. J.B. Gassner put our bodies on the German fair circuit. At a circus convention in Vienna, he auctioned the monstrous Madonna and her brute baby. For a quarter of a century we passed from hand to calloused hand for cash.

The new century felt the old disgust for a pair of creatures with hair where hair should not be. In ‘twenty-one, Haakon Lund bought us for his Norwegian chamber of horrors. That was the year my name was divided from my body. ‘Julia Pastrana’ was not listed on the bill of sale. The new generation of shilling-payers did not think me real, but a diabolical confection of horsehair and leather, a relic of more barbarous times before Modernity, its brute lines, featureless towers, slot windows, slack chairs and inhumanly pale renders. I thought Modernity a diabolic confection of vanity and laziness. Modernity and I agreed to disagree.

When the Nazis thundered into Norway they ordered us destroyed. But Lund made them believe an Ape woman tour would line the Third Reich’s coffers, while showing to a hairy nicety miscegenation’s awful perils. On the strength of the world’s worst ever idea, my monkey son and me outlasted the war and the pale blue eyes that despised us up and down the Rhine.

‘Fifty-three and the good times were over for monsters. Lund stored his chamber of horrors, including us, in a warehouse outside Oslo. Rumours spread of a ghastly ape haunting the midnight dust. Teenage horror-seekers broke in, surrounded us, opened their mouths in ‘O’s and screamed till I thought our glass would shatter. Lund’s son Hans saw new money in the teenage stories in the press. He set us back to earn.

But now at last, someone remembered the old ape lady Julia Pastrana. In ‘sixty-nine, Judge Hofheinz, collector of curiosities, hired detectives to hunt down the Female Nondescript. Hans set up a bidding war for our corpses, only to withdraw from the sale to profit from the press’s frantic delight. He put us on the circus routes of Sweden and Norway, then shipped us to America. Here a New Age public finally found its conscience and cried out against the poor corpses paraded. So Hans rented us to Swedes. Again I travelled until people, month by month, grew ashamed of seeing me. I settled into years of peaceful warehouse dust, tender as fingers on my cheek.

Then the vandals came. They tore off my son’s arm, punched his little jaw, threw him in a gutter where the mice ate him. By the time he was found, he was in small scraps. I was left alone in my glass case looking at his empty pedestal, year on year.

‘Seventy-nine, I was stolen in the night. Once more, I was separated from my name. Children found my arm protruding from a ditch. The police pulled an entire woman, with hair where it should not be, from the mud and leaves. A crime against a woman dead a hundred years could not be chased. And who would charge dead Theodore with selling his wife, living and dead?

They delivered me to the Norwegian Institute of Forensic Medicine. I lived in its basement, a friend to mould and unsolved case files.

Nineteen-ninety, I felt the old cold draft of a journalist swooping down on me. I sold more newspapers when my ugly tale was knitted to my old body again.

Norwegian priests pressed for a Christian burial. A compromise – a sarcophagus in Oslo’s Museum of Medical History, a small DNA extraction first.

Twenty-twelve they sent me back Mexico, a burial my home country. A Roman Catholic mass was said over me. My coffin was borne to the cemetery in Sinaloa Province where I had begun. Instead of dirges the band played jaunty music, as if it were a fine thing to lay the dancing baboon-lady in earth at last.

But I shall hardly rest in peace.

For why was I repatriated to a backwater I left gratefully at twenty? Was I not celebrated worldwide, a star of the stage, the newspapers’ darling? Should I not have had a hollow in the actors’ graveyard in Covent Garden? Or lie with the other famous clever ladies in Saint Pancras field?

Or better still, I should have been allowed to sleep beside my Theodore, to lie and lie beside him for immemorial nights; to watch him gyre in his grave as the muscles died and shrank and danced his bones on leathery strings. Everything would drip from us, except my deathless hair, wrapped around his every place, a black wreath, a furring, a stirring of living hair everywhere on Theodore, everywhere my hair should justly be.

↧

The Boy from Titchmarsh and the Queen's Tiara

I was delighted to see the Queen’s choice of tiara when she entertained President Michael D. Higgins at Windsor Castle last month. Not that I’m particularly a connoisseur of tiaras, but I happened to know a bit about the Vladimir from researching my just-completed novel, The Grand Duchess of Nowhere.

![]()

How the Vladimir came into the possession of the Queen is quite a saga. It was originally the property of Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna, the wife of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich. Grand Duke Vladimir was an uncle of Tsar Nicholas II. The Grand Duchess was known familiarly as Miechen, and she was an Olympic-standard collector of gems, dropping into Faberge and Cartier as you and I might swing by the supermarket. She also had a very generous husband who understood that after giving birth the thing a woman most longs for is a parure of diamonds or sapphires.

Miechen had three sons and one daughter, all intended to be the eventual recipients of her jewel collection, but history took a different turn. By early 1917 Miechen, along with many other Romanovs, had headed south to Crimea, away from what they supposed were temporary political disturbances in St Petersburg and Moscow. That Miechen left behind most of her jewels in the Vladimir Palace is evidence enough that she believed she’d be going back.

As the revolution gathered pace Miechen began to accept that she was facing exile and with it the pressing need for ready money. She needed her jewels, but how to retrieve them from a city now under the control of the Petrograd Soviet? Enter stage left Bertie Stopford, an Englishman who preferred to speak French, a vicar's son from Titchmarsh in Northamptonshire, neither soldier nor diplomat but somehow free to move around wartime Russia and be an entertaining friend to women like Grand Duchess Miechen.Miechen had three sons and one daughter, all intended to be the eventual recipients of her jewel collection, but history took a different turn. By early 1917 Miechen, along with many other Romanovs, had headed south to Crimea, away from what they supposed were temporary political disturbances in St Petersburg and Moscow. That Miechen left behind most of her jewels in the Vladimir Palace is evidence enough that she believed she’d be going back.

A plan was quietly hatched. Stopford and Miechen’s son Boris, dressed as boiler repair men, entered the Vladimir Palace by the tradesman’s entrance, made their way to Miechen’s boudoir and sprang her jewels, including the pearl drop Vladimir tiara, from her safe. The precious items were taken out of the palace in tool bags. How they were spirited out of Russia is still unclear, perhaps by diplomatic courier, courtesy of the British Embassy, perhaps concealed in someone’s clothing. A tiara would certainly have been difficult to secrete in one’s bloomers.

A plan was quietly hatched. Stopford and Miechen’s son Boris, dressed as boiler repair men, entered the Vladimir Palace by the tradesman’s entrance, made their way to Miechen’s boudoir and sprang her jewels, including the pearl drop Vladimir tiara, from her safe. The precious items were taken out of the palace in tool bags. How they were spirited out of Russia is still unclear, perhaps by diplomatic courier, courtesy of the British Embassy, perhaps concealed in someone’s clothing. A tiara would certainly have been difficult to secrete in one’s bloomers. However it was done, Miechen’s jewels made it out of revolutionary Russia. Their value though was greatly diminished in a market flooded with gems belonging to exiled Romanovs. Cheaper pearls were becoming available too, from Japan. Fortunately for Miechen she didn’t live long enough to feel the pinch of their devalued worth, but after her death her children had to get whatever they could for them in order to pay off her debts. They were disposed of discreetly. Wealthy potential buyers were approached. Psst. Want to buy a diamond and pearl tiara, one careful previous owner?

The Vladimir was acquired by Queen Mary, the wife of King George V, and it was her idea to use some emeralds she had lying around and have them mounted as alternatives to the pendant pearls. 'To ring the changes', as the fashion editors say. When Queen Mary died her granddaughter, our present Queen, inherited the Vladimir tiara, with its two sets of pendants, and it was the emeralds that were aired at Windsor in April.

As for Bertie Stopford, I don’t know if he was rewarded for his derring-do. Perhaps the gratitude of a Romanov Grand Duchess was all he ever wanted. He lived out the rest of his life, mainly in Paris, with no visible means of support except lots of dinner invitations and the occasional commission from buying and selling antiques. He was a gadfly and name-dropper par excellence, but when he died in 1939 his estate only ran to the cost of a 30 year lease on a plot in the Bagneux Cemetery. In 1970 the man who rescued the Vladimir tiara ended up in a communal grave. His world and his so-called friends had faded away. But his true wealth, of course, were his memories, as recorded in his Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-17.

↧

Jack-in-the-Green and the living ritual, by H.M. Castor

|

| Jack-in-the-Green, Bristol, 2014 (Note the face above the yellow flower!) [All photos copyright H.M. Castor unless otherwise labelled] |

[O]ne of my colleagues [was] asked by a friend about our collaboration with [Joseph] Campbell: "Why do you need the mythology?" She held the familiar, modern opinion that "all these Greek gods and stuff" are irrelevant to the human condition today. What she did not know — what most do not know — is that the remnants of all that "stuff" line the walls of our interior system of belief, like shards of broken pottery in an archaeological site. But as we are organic beings, there is energy in all that "stuff." Rituals evoke it.

(Extract from Bill Moyers’ introduction to The Power of Myth

– a series of conversations with Joseph Campbell.)

Compared to the lives of our ancestors, our lives in the 21st century are very short on ritual. Shout me down if you will, but I’ll hazard a guess that, unless you attend a daily religious service, are a warden of the Tower of London (say), or – at certain times of the year – happen to be the Queen, you are likely to take part in what might be called a ritual much less frequently than the vast majority of your forebears. On the power of ritual, and what we might have lost as a society through its decline, there is much to be said – I won’t go into it here. Instead, I’d just like to tell you what happened to me the Saturday before last.

It was the first Saturday in May – the day, I’d (just) heard, when the Bristol Jack-in-the-Green would be making his annual appearance. Setting off in the morning, he would spend several hours processing through town, and by mid-afternoon would be passing along the main shopping street near where I live. From there, he would go on to be ritually ‘slain’ on a common not far away.

I didn’t know Bristol had a Jack-in-the-Green.

I didn’t, if truth be told, know what a Jack-in-the-Green was.

Hastily I reached for my copy of Steve Roud’s excellent book The English Year: a month-by-month guide to the nation’s customs and festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night. Roud told me that, from the late 18th to the early 20th century, Jack-in-the-Green had appeared as “an integral part of the [May Day] celebrations put on by chimney sweeps,” during which they collected money “to help see them through the summer, the lean period of the trade.”

And there was a vivid description of Jack’s appearance, from A.R. Bennett’s memoir of a south London childhood in the 1860s:

A lusty sweep — for strength and endurance were necessary for the due performance of the part — covered himself down to the boots with a circular wicker frame of bee-hive contour, carried on the shoulders, and terminating in a dome or pinnacle above his head. The frame was entirely concealed by green boughs and flowers… A small window gave egress to his gaze, but was not very obvious from without, and one seldom caught a glimpse of the perspiring countenance within.

[quoted in The English Year by Steve Roud, p.210]

The historian in me pounced on the German connection with interest: since Jack-in-the-Green appeared in England in the late 18thcentury, when many things from Germany were in vogue, was he a straightforward import? Was he connected with chimney sweeps in Germany too? How far did the tradition there date back?

But I didn’t get any further with this – I had to go and see the real Jack. With my (rather reluctant) 10-year-old daughter for company I set off, and on the main street we soon heard drums signalling Jack’s approach.

An account from 1900, quoted in The English Year, said that Jack-in-the-Green looked like “a big bush… bobbing up and down” – I soon saw that this was a perfect description. Jack bobbed, jigged and spun around while his band of green companions (I’ve seen them called ‘bogeys’ or ‘bogies’ on some websites) played instruments, sang, walked backwards to warn him of upcoming obstacles, and daubed the noses of any willing bystanders with a smear of green face-paint.

|

A 'bogie' at Jack in the Green, Hastings 2004 by Nicklott (Own work) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Some of Jack's followers in Bristol this year were younger than others... |

The procession halted at one point for a bit of morris dancing (with Jack twirling in the centre of the circle), and then progress was resumed. Jack was picking up a fair few followers as he went, but plenty of other people he passed just waved, grinned or took pictures.

My daughter and I hadn’t planned on following him, but we were beguiled, and a short while later found ourselves accompanying Jack onto the common.

In the middle of the common Jack stopped, surrounded by his green companions and a circle of onlookers. He moved around the crowd, bobbing little bows here and there, approaching people as if investigating them… but any attempts at escape were blocked by the ‘bogeys’ with admonishing shouts of “Now, Jack!”

There was more dancing… and the recitation of a poem about ‘the Green Man’.

And then, after a swift surreptitious escape was made…

…Jack was hoisted into the air…

...toppled...

… and ‘slain’ with ferocious jabs of a stick.

After that the kids piled in (my daughter included) and pieces of Jack’s greenery were pulled off and handed out for everyone to take home.

So, what had we just witnessed? A bit of silliness? A meaningful tradition? Given the inclusion of a poem about the Green Man, some people – The English Year’s author Steve Roud included – might not have approved.

So, what had we just witnessed? A bit of silliness? A meaningful tradition? Given the inclusion of a poem about the Green Man, some people – The English Year’s author Steve Roud included – might not have approved.

[Jack-in-the-Green’s] history and reputation have been sadly misrepresented. Despite the fact that Jack dates from the late eighteenth century, lasted for little more than 150 years, and was an urban rather than rural custom, he is routinely claimed as an ancient pagan tree-spirit, or as a personification of a vegetation god who dances to welcome the spring. He has also become inextricably tangled up in the complex modern persona of ‘the Green Man’, that powerful symbol used by the romantic wing of various eco-friendly and New Age groups. He has thus been absorbed into the amorphous blend of foliate heads (as the Green Man carvings in churches were previously called), medieval wildmen, Robin Hood, Gawain and the Green Knight, and anything or anyone else ‘green’, who are all now equated with vegetation and nature spirits. Needless to say, there is not the slightest evidence that Jack-in-the-Green has any connections with these other characters, but it is probably impossible now to rescue him from such dubious company.

[The English Year by Steve Roud, p.212]

With my historian’s hat on, I do appreciate the important distinctions Steve Roud makes, but the Jack-in-the-Green procession I saw was not performed as a historical re-enactment – it was performed as a living ritual. And a question springs to mind: what is wrong with letting Jack-in-the-Green evolve? May Day celebrations have been many and varied over the centuries, and new versions of them have always developed – surely – out of what has gone before. Jack-in-the-Green did not appear in the 18thcentury out of the blue (as it were); in making such a feature of green boughs and flowers the chimney sweeps were continuing a much older tradition of welcoming in the spring/summer, and in symbolising this new season in the form of a figure, were they not drawing inspiration from other figures? Strictly speaking, it might be ‘wrong’ to equate Jack with ‘the Green Man’, but he was a green man, a figure of nature, a figure of the May, without doubt.

Would it be better if, today, Jack’s followers smeared their faces with chimney soot and carried sweep’s brushes, since that would be sticking to Jack’s specific and particular origins? Personally, I don’t think so (though neither am I objecting, if they want to). The heart of the ritual is the marking of May Day, and I think you can let some bath water go while still hanging on to the baby.

I also think it’s important to remember that legends, myths and symbols inevitably shift and alter as they are viewed from different perspectives in different eras. Indeed they mustif they are to continue to carry any meaning. In the current climate (literal and metaphorical) it is not surprising that a symbol like ‘the Green Man’ is gaining new popularity, and while any claims made to a straightforward lineage might be mistaken, it is not true (either) to say that the Green Man is a new invention. We have a soup of traditional figures and stories that – for centuries – has been energetically stirred. And we must go on stirring, because setting symbols in aspic will eventually render them lifeless and irrelevant.

So, for me, the point lies in asking ourselves whether a symbol or a ritual still carries some living energy – can it still mean something to us? I don’t know about you, but the coming of sunshine and warmer weather has a profound effect on me (not as profound as if I had lived before central heating and tarmacked roads, but profound enough nevertheless). And to my surprise, I found last week that doing something more to mark summer’s arrival than putting away my jumpers and saying ‘What lovely sunshine’ could have meaning. I wasn’t the only one.

My 10-year-old daughter, as I mentioned, had been reluctant to come with me to find Jack-in-the-Green. Go and look at a man dressed in leaves? She didn’t see the point. But at bedtime that night she told me it had been ‘the best thing ever’. Why? Neither of us could quite put our finger on it. Something to do with the feeling of community? Something to do with the fact that the only point was the ritual itself (no presents, no sweets, no commercialization!)? Something to do with how it was playful, symbolic, silly and serious, all at once? We didn’t know. But we’d gone with no expectations, except of seeing a curiosity. And we’d come back having – rather mysteriously – loved it.

Thanks to Mike Slater, there's footage on Youtube showing the whole of the final part of Jack's journey in Bristol on May 3rd 2014, including the morris dancing and the ‘slaying’. It can be seen here (the action begins at 2:09 mins).

↧

↧

LADY CROOKBACK – on disability and invisibility in historical fiction. By Elizabeth Fremantle

|

| Lady Mary Grey |

My own daughter was paralysed as a baby and for many months we believed she would never walk. Happily she did, but that experience fuelled my desire to give a voice to one of history's invisible women and to articulate something of the kind of life she might have led as both court insider and outsider. One comes across the occasional man with physical differences in historical fiction: Bucino the dwarf of Sarah Dunant's In the company of the Courtesan, George RR Martin's Tyrian Lannister and polio victim Tomas Ashton of Rosie Allison's The Very Thought of You. All these characters play a pivotal part in their respective narratives, with Ashton as a damaged romantic lead in the mould of Jojo Moyes's quadriplegic hero in Me Before You, Lannister as a key character and Bucino as the protagonist of Dunant's novel. But there is a distinct absence of women with disabilities at the heart of historical fiction. It seems that women are allowed flaws of character, and a prevalence of women with psychological challenges can be found, but bodily flaws seem to be taboo. Looking to the past for literary examples offers little. There is the wheelchair-bound Edith in Stephan Zweig's wonderful Beware of Pity and a number of tragic girls like Beth in Louisa May Alcott's Little Women and Love For Lydia Springs to mind too, who are defined by debilitating illness but it is hard to find empowered women who do not conform to the physical norm. It is for this reason that I chose to take that ambassador's grim appraisal at face value when creating the character of Mary Grey. I didn't want to tone down her disabilities or blur them in any way and felt it was important for her to live on the page as she was in life and allow her, in some small way, speak for all the invisible women of her time.

|

| The Infanta of Spain with her dwarf |

Here's a short extract from Mary Grey's story. In it she is only nine-years-old and reeling from the execution of her beloved sister Jane.

Here's a short extract from Mary Grey's story. In it she is only nine-years-old and reeling from the execution of her beloved sister Jane.I hand my gown to Magdalen, who holds it up, saying with a smirk, 'How does this fit?' She dangles it from the tips of her fingers away from her body.

'This part,' I explain, pointing at the high collar that has been specially tailored to fit my shape, 'goes up around here.'

'Over your hump?' Magdalen says with a snort of laughter.

I must not cry. What would my sister Jane have done, I ask myself. Be stoic, Mouse, she would have said. Let no one see what you are truly feeling.

'I don't know why the Queen would want such a creature at her wedding,' Magdalen whispers to Cousin Margaret, not so quiet that I can't hear.

I fear I will cry and make things worse, so I think up a picture of Jane. I remember her saying once: God has chosen to make you a certain way and it cannot be without reason. In his eyes you are perfect – in mine too. But I know I am not perfect; I am so hunched about the shoulders and crooked at the spine, I look as if I have been hung by the scruff on a hook for too long. And I am small as an infant of five, despite being almost twice that age. Besides it is what is in here that matters; in my mind's eye Jane presses a fist to her heart.

Sisters of Treason will be published on 22nd May

ElizabethFremantle.com

↧

Strange Fruit, Ida B Wells (and Kate Beaton again) Catherine Johnson

In the 19th and the early part of the 20th centuries lynching was a not uncommon occurrence in the Southern States of America. Of course lynching is not unique to this part of the world. In every country at one time or another the powerful have extracted summary punishments on the less powerful with or without reason.

But in the Southern states, right up until the civil right movement, lynchings were public spectacles, crowds would gather, postcards were produced as souvenirs, members of the crowd might point out to interested relatives exactly where they stood in relation to the victim. Or as in the picture below, from a 1930s lynching, smile for the camera. By the way, the girls are holding shreds of murdered men's clothes (two were hung in this case) which were highly prized souvenirs.

|

| From Without Sanctuary Allen, et al. |

Ida B Wells was a firebrand and a blazing star who deserves recognition here, as well as in the USA. She was born in 1862, a slave, just months before the emancipation act in 1863. Her parents believed in education and she was sent to college, leaving only when her parents and baby brother died in order that she could work as a teacher and support her remaining siblings. She later attended evening classes at Fisk University and was the first black woman to write for a white newspaper. She toured the world speaking out against the horrors of lynching after her co workers in a community store she set up were lynched. (The stores' white owned competitor was not happy).

Not only that she refused to give up her seat in a railway carriage and protested in 1893 against the exclusion of blacks from the Chicago World Exposition.

And that's not all - she was one of the first women in public life to actively keep her own name and not take her husbands' after marriage. She had four children, wrote a heap of books and set up the National Association of Colored Women, which became part of the NAACP.

Her later life was concerned mostly with education and writing and she died, aged 68 in 1931, as many of us might want to in mid sentence, writing a book.

|

| Ida B Wells by Kate Beaton |

If you'd like to learn more

her writing is free here

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Southern-Horrors-Lynch-Law-Phases-ebook/dp/B0084CGSRA/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1399988558&sr=1-2&keywords=ida+b+wells

And there's a rather wonderful biography by Mia Bay : To Tell the Truth Freely

http://us.macmillan.com/totellthetruthfreely/MiaBay

And because there is never enough Kate Beaton ever there's a link to a series of comic strips about Ida B Wells below.

http://www.harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=356

Catherine Johnson's latest book is Sawbones, an 18th century forensic murder mystery.

↧

Roads for Runaways

by Marie-Louise Jensen

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*) Researching 18th century roads in England for my most recent book was a fascinating learning experience. I'd read of poorly maintained roads, of course, and of toll gates and pike roads, but they were all vague terms that swirled about in my mind rather. I'm far from an expert now, of course, but I did learn some interesting things.

Researching 18th century roads in England for my most recent book was a fascinating learning experience. I'd read of poorly maintained roads, of course, and of toll gates and pike roads, but they were all vague terms that swirled about in my mind rather. I'm far from an expert now, of course, but I did learn some interesting things. What is interesting is, that it wouldn't be the first time that roads have been put into private hands in the UK.

In the 17th century, most of the roads here were in such an appalling state that travel was a penance. It's hard to imagine just how bad appalling is. Imagine the narrowest, most rutted and muddy lane you've ever seen, completely impassible for cars, send a riding school along it with big trains of horses every day, add a few herds of cattle and you are probably accurately visualizing one of England's main 17th century thoroughfares.

Maintaining the roads was the responsibility of the parish through which they ran. Each parishioner was obliged to give a number of days labour per year to maintain the road and a local squire would be appointed to oversee it.

As with any voluntary, unpaid task, adherence was patchy (like the roads!) And for practical and financial reasons only local materials were used, so in boggy areas, you'd get boggy roads.

Another huge problem was that in a populous parish with a little used road, the road would probably be fine. But there were sections of the great North Road, for example, that passed through scantily inhabited parishes where it would have been a full-time job for the few residents to maintain the roads adequately.

Thus as travel increased, with a growing economy and early industrialization, the system didn't work.

In the early 18th century, the government began handing over sections of road which were to be maintained in return for charging travellers toll.The Turnpike Trusts, and the turnpike roads, were born.

Initially, this scheme was so successful that it was quickly expanded. The turnpike roads helped speed up travel considerably.

In the long run, many of the problems we see today in privatized services surfaced. Some trusts maintained their roads meticulously, others pocketed the money and let the roads go to rack and ruin. Travellers were furious at paying toll for such roads and eventually road maintenance was taken into government hands.

The road my runaway flees on is the Great Western Road, or what was also known as the Bristol Road or the Bath Road which ran westwards from London. Although this, of course, is only the start of her travels. But more about that in later posts.

Runaway is published by Oxford University Press on 5th June 2014

↧

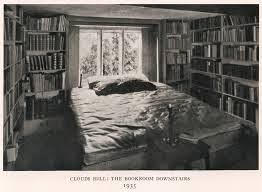

Writers' Houses 2: Lawrence of Clouds Hill - by Sue Purkiss

When I first saw Lawrence of Arabia, there was one particular scene that caught my attention. Lawrence (aka Peter O’Toole) was making a point about mind over matter. He lit a match, and he held his finger within the flame. He gazed at it, bright blue eyes intent, face unmoving. Then, quietly, he said something to this effect: “It’s not that I don’t feel the pain. It’s that I don’t allow myself to show it.”

This was interesting. It spoke of a man with striking powers of concentration, self-belief and self-discipline – an ascetic. A man following the beat of his own drum, not that of others.

In civilian life Lawrence

I knew little more about him than this. But a few weeks ago, I went to Clouds Hill, his retreat in Dorset , and there I learnt a great deal more.

Clouds Hill is a tiny white-washed cottage in a clearing in the woods near Bovington, where there is and was a Tank Corps camp. After his wartime activities, his post-war political campaigning on behalf of the Arabs, and the completion of his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence

Built in 1808, the cottage was in desperate need of essential repairs. To fund this work, Lawrence sold the gold dagger which had been made for him in Mecca Dorchester I wrote about last month. I don’t think he would have known Emma, but he did become good friends with Thomas Hardy and his second wife, Florence

|

| The upstairs room |

So he had a large window put in upstairs which would give him enough light to write by. He had very definite ideas about interior design, and was influenced by the ideas of William Morris: there was a certain harking back to mediaeval, monastic simplicity. Objects were designed to fulfil a function, not simply for the sake of their appearance. Clouds Hill had no paint or wallpaper; it was decorated with wooden shelves and panelling and undyed leather hangings. There was no gas or electric light; nothing but candles. Friends – including E M Forster, George Bernard Shaw and his wife, and friends from the ranks - would come and talk, and listen to the music he played on his state-of-the-art phonograph, and be offered tea and tinned snacks.

Later, when he started to make good money from his writing, he did more to the cottage – but it never became a conventionally appointed house. He didn’t want a kitchen, but he did get the downstairs damp-proofed and created a room with a large, leather-covered day-bed next to the small window, for reading in the daytime. At night, he used a chair with an integral table and sconces for candlesticks, in which he sat by the fire, surrounded by his collection of hundreds of books, many of them given to him by their writers. He also contrived a system for bringing and heating water to the bathroom he put in also on the ground floor – ‘Give me the luxuries,’ he declared, ‘and I will do without the essentials.’ (Such as an indoor toilet!) He also bought new varieties of rhododendron to plant on the wooded slopes around the cottage, and built a thatched cottage for his beloved Brough motor cycle.

Later, when he started to make good money from his writing, he did more to the cottage – but it never became a conventionally appointed house. He didn’t want a kitchen, but he did get the downstairs damp-proofed and created a room with a large, leather-covered day-bed next to the small window, for reading in the daytime. At night, he used a chair with an integral table and sconces for candlesticks, in which he sat by the fire, surrounded by his collection of hundreds of books, many of them given to him by their writers. He also contrived a system for bringing and heating water to the bathroom he put in also on the ground floor – ‘Give me the luxuries,’ he declared, ‘and I will do without the essentials.’ (Such as an indoor toilet!) He also bought new varieties of rhododendron to plant on the wooded slopes around the cottage, and built a thatched cottage for his beloved Brough motor cycle. Sadly, he met his death on the Brough. In 1935 he was all set to retire from the army and live full-time at Clouds Hill; but riding back from the camp one day he had to swerve to avoid two boys on bicycles, and he came off. He died a few days later, and is buried in the churchyard at nearby Moreton. (The church there has the most beautiful engraved windows, created by Laurence Whistler – not to be missed.)

A quiet but insightful guide told us more about Lawrence Ireland , had abandoned his first wife and family and come to live in England Oxford , where Lawrence Carchemish in Syria , digging with Leonard Woolley, before being posted to Cairo

Two of his brothers were killed in the war, his father died just afterwards in the flu epidemic, and then his mother and another brother went to China Lawrence

It’s a green, peaceful, quiet place: a place, as Yeats puts it, ‘where peace comes dropping slow.’ A world away from the desert and the fates of nations, and an insight into a remarkable and unusual man.

↧

↧

TYPING A WAY TO THE TOP by Penny Dolan

How often does one understand something you should have known all along?

How often does one understand something you should have known all along? While working on my Mary Wollstonecraft story for the Daughters of Time anthology, I started thinking about education for girls, and especially my own mother’s education. So today, because May was her birthday month, let me tell you a little about the schooling of Evelyn Gladys Rose, fourth child and only daughter of an army family.

I knew where she went to school, because I went to the school myself : Noel Park School, Wood Green, North London. The school is one of the generation of imposing “triple-decker schools” familiar in urban areas, built to last. The healthily high-ceilinged rooms have large windows to let in plenty of light but set well above any inattentive child’s eye level. The schools have large halls and, as any current staff would agree, a quantity of staircases. Sometimes one can still find “Boys” and “Girls” carved in stone above the once-segregated entrances. Noel Park School, when I knew it, still had a “Boys” playground and a “Girls & Infants” playground, divided by a high brick wall and each with its own outside lavatory block. We never went to the top of the school..

In 1921, the school-leaving age was raised from 12 to 14, but it was the 1926 Hadow Report on Education and Adolescents that led to pattern of classrooms that my mother knew.

Her Noel Park School taught Infants on the ground floor (5-6 years) Juniors on the middle floor (7-11years) and the Seniors (12-14) up on the top floor. The division at age 11 was chosen for practical reasons. Some of the boys,

I believe, went to a nearby secondary school, where the emphasis was on technical education.

Her Noel Park School taught Infants on the ground floor (5-6 years) Juniors on the middle floor (7-11years) and the Seniors (12-14) up on the top floor. The division at age 11 was chosen for practical reasons. Some of the boys,

I believe, went to a nearby secondary school, where the emphasis was on technical education.

There was, however, one way out of Noel Park. After a year, able children could win a scholarship to Glendale Grammar School. Among my mother’s “treasures” is the letter offering her a coveted place, but - a familiar tale of the times - she did not go. The uniform was expensive and the overall cost would be too much.

My grandfather, she hinted, refused to give his permission. One of the reasons she gave was that it was because she was a girl. My mother only mentioned this disappointment a couple of times, but I wonder if the incident drove her on all her life. So she studied typing and shorthand, becoming a formidably accurate typist, and during World War II, she left home and joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force and was in the typing pool at High Wycombe, across the corridor from the office of Arthur “Bomber” Harris.

My grandfather, she hinted, refused to give his permission. One of the reasons she gave was that it was because she was a girl. My mother only mentioned this disappointment a couple of times, but I wonder if the incident drove her on all her life. So she studied typing and shorthand, becoming a formidably accurate typist, and during World War II, she left home and joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force and was in the typing pool at High Wycombe, across the corridor from the office of Arthur “Bomber” Harris. My mother never really stopped working. Her typewriter was her identity. With her toddler in the back seat, she cycled the country lanes of then-rural Cheshunt and Nazeing, collecting and delivering freelance typing.

Later, she got a job as a typist and then secretary at the impressive Woodhall House, home of the local gas company but now the Wood Green Magistrates Court. One afternoon, aged around eight, I went up the drive, through those polished doors, edged up to the Reception desk and asked to see her.

Later, she got a job as a typist and then secretary at the impressive Woodhall House, home of the local gas company but now the Wood Green Magistrates Court. One afternoon, aged around eight, I went up the drive, through those polished doors, edged up to the Reception desk and asked to see her. In an era when female office staff hid any hint of “children”, my mother the secretary was not at all pleased to see my after-school face, especially when my reason was too complicated to explain. I think I had wanted to prove to my friend that my mum really did work in such a palatial building.

My mother kept at it. Eventually became the personal secretary to one of the top “Gas Men” up in London and after retirement worked on at the St John Ambulance Brigade Headquarters. Such determination! Even as she lay dying, she was struggling to get out of bed to go to work. (What would I get out of such a bed for, I wondered? Soon after that moment, I started trying to write.).

My mother had always wanted me to achieve, too. She wanted me, her daughter, to have the education she hadn’t had. She was the one who was keen on my education, the one who pulled all the strings she could to get me into the local single-sex Convent Grammar School. She was also the one who picked up the pieces between one disastrous school incident and another, the one who pushed me into becoming a teacher. Before the second wave of feminism, my mother was determined to show everyone that girls are just as good as boys and just as deserving of their education and place in the world. Maybe she echoed some of Mary Wollstonecraft's ideals?

However, back to that WAAF typing pool. I recently met up with my mother’s best friend. Shortly afterwards, she sent me two pages from her autograph book of that time. On the left page is a verse by Johnnie, a man who was often calling in to the pool, giving his view of the WAAF typists. On the opposing page is my mother’s spirited reply. Both verses are below.

The Song of the Airman

Beauteous maidens, garbed in blue,

Hindering those with work to do,

Drawing pay for doing naught,

Doing things they didn’t ought,

Powdering noses, apeing fashions,

Eating much more than their rations,

Affected girls with silly laughs

Useless, muddling, blundering W.A.A.F.S.

The W.A.A.F.S Lament

Stalwart he-men, big and strong (?)

Boasting, bragging all day long,

Thinking they do all the work,

Walking round with saintly smirk,

Trying to behave but finding

This ordeal much too binding.