![]() |

| The Oseberg Ship |

A guest post today from one of our valued History Girls Reserves, Susan Price. It will fascinate anyone who has seen the reconstruction of the longship at the Vikings exhibition in the British Museum.This, the Oseberg ship, has been called the most beautiful ship ever built. Today, of course, it’s priceless. When it was built, it was, to say the least, ‘a high-status artefact.’ But it’s hard to form an idea of just how valuable it was when first made.

In the Viking Age, cold and hunger, even starvation, were always near: just one bad season away.

To keep hunger at bay, the time and labour of many people was needed. Fields had to be planted, weeded, harvested. Animals had to be tended, fish and game caught. Fuel was constantly needed, for cooking and brewing, and had to be found or cut, and stored for winter. Food had to be carefully stored, to preserve it: smoked, dried, salted. Milk had to be turned into cheese and butter. Wool and flax had to be spun into thread and woven into cloth. Barns had to be kept in repair, walls and tools mended.

This ship represents months, perhaps years, of labour that produced neither food nor fuel. Indeed, it consumed food and fuel, as the shipwrights had to be fed and housed by the labour of others. A ship of this quality wasn't built by farmers in their spare time.

![]() |

| The prow |

The Vikings were expert shipwrights, but the Oseberg isn't merely utilitarian. It's exquisite, almost an art object. Look at the lines of her. Look at that beautiful prow, like a piece of sculpture. Look at the carving, probably once painted and gilded.

![]() |

| The carving |

This ship was an expression of staggering wealth, status and power. They built her, at all this expense, and then they threw her away: – they buried her.

Oslo's other great ship, the Gokstad, was a working warship before she was used in a ship-burial, but the beautiful Oseberg doesn't seem to have been much used. (Though, as ever, interpretation changes. It used to be said that the Oseberg wasn't sea-worthy, because a 1980s replica sank when taken into open sea. It was argued that the ship was merely 'a pleasure yacht,' intended only to cruise up and down a sheltered fjord. However, the replica was based on the original reconstruction, done soon after the ship’s discovery in 1904. As with the first reconstructions from dinosaur bones, mistakes were made, and pieces discarded because they ‘didn’t fit.’ A modern replica is now being built, based on far greater knowledge of Viking ships learned from Roskilde. This new Oseberg is confidently expected to be as sea-worthy as any other Viking ship.) When excavated, the Oseberg was found to hold everything needed by a noble household: wooden brewing tubs, for instance, bound with iron, and the kind of small wooden bucket from which drink would be ladled into horns at table. Ladles. Cauldrons. Tapestries. A loom. A large bed. Carts and sledges. Horse equipage.

In a further expression of power and wealth, fifteen horses, four dogs, two small cows and some pigs were buried in and around it. All had been beheaded.

![]() |

| One of the wagons |

What great king lay at the centre of this wealth? None. The ship sailed for the Other World carrying two women. One woman was originally thought to have been aged between 25 and 30 at her death. Her skeleton had been damaged and some parts were missing. She had been clothed in a fine red wool dress with a lozenge pattern, and a fine white linen headdress.

The other, complete, skeleton had been a woman between 70 and 80, about five feet tall, with a crooked spine. Her bones showed signs of arthritis. She was dressed in plain blue wool, with a headdress of wool. These differences in dress arguably show a difference in status.

The original excavators reasonably concluded that at least one of these women had been extremely wealthy, possibly a queen. Since the ship dated to about 834 AD, it was suggested that she was Queen Asa. The name of the mound, Oseberg, was, it was suggested, possibly derived from 'Asa's Mound'.

The younger woman was supposed to be the queen's handmaid, possibly a slave who volunteered to join her queen in the grave, or was killed to accompany her. (Several Viking graves have been found where one occupant had been murdered – or sacrificed, depending on your point of view.)

In support of this theory was the fact that the younger woman's skeleton was damaged and her collar-bone broken - injuries possibly caused by a violent death.

This explanation never satisfied everyone. 'Oseberg' means, some maintained, 'The Gods' Mound.'

The bones from the ship were re-examined in 2007, and the new report said that the younger woman had not been 25-30, but nearer 50. Nor had she been violently killed. Her broken collar-bone had been healing for several weeks before she died. The other damage to her skeleton had been post-mortem.

Both women's diets had included a high proportion of meat, rather than the more normal diet for their time and area, with the protein supplied mostly from fish. The younger's teeth showed signs of wear consistent with her having used a metal toothpick - a luxury item. This suggested that both were of high status.

Were they mother and daughter? Not enough DNA could be collected from their bones to settle this question, but the older woman's bones showed that, besides arthritis, she had suffered from cancer, which had probably killed her. They also showed that she'd had a hormonal disorder, Morgagni’s Syndrome, which would have given her a masculine appearance, perhaps even a beard.

The theory that the older woman had been a queen, and the younger her slave was further weakened by the fact that the grave had been robbed during the Medieval period, and all metal items stolen. It was during this robbery that the younger woman's skeleton was damaged. Surely her skeleton had been broken by the robbers because it had been decked in jewellery of precious metal? Which would indicate that she, rather than her older companion, was of the higher status during life.

Other details: the two women lay on a great bed, itself a high status item. It had been carved with horses’ heads. One woman had a leather pouch containing cannabis seeds. Among their equipment was a long distaff – a tool strongly associated with women, it’s true, but also, for that very reason, with the Goddess Freya and the volvur, the pagan priestesses.

![]() |

| Carving on the wagon |

The carts and sleighs on the ship had been assumed to be practical, working equipment, something needed by a great household. Researchers taking a new look at the grave goods pointed out what had always been plain: they were too small and shallow, and too highly decorated, to have ever been practical. Such carts, however, have a long association with pagan gods. The Romans recorded that the Germanic Goddess Nerthus was driven in procession in a sacred cart. The sagas mention a priestess of Frey accompanying an image of the god, which is carried in a cart. Think of the many religious ceremonies today, where a figure of a deity is drawn in procession on some highly decorated vehicle.

So were the women in the ship priestesses? And if so, who did they worship?

![]() |

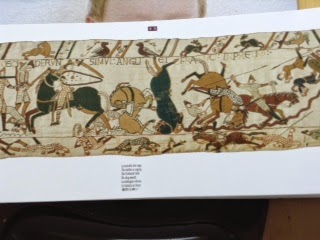

| Replica tapestry from Oseberg |

A grave chamber was originally built over the women, and the walls were hung with tapestries – another declaration of status and wealth. The tapestries show women driving carts. Another image showed nine men hanging from trees, with three female figures standing nearby. It's recorded that, in the sacred grove at Uppsala, a festival was held to celebrate the Disir, the divine female powers. Every nine years, we are told by a Christian source, for nine days, nine males of every available species - including human - were sacrificed by hanging from the groves' trees.

Does the tapestry depict this scene? And if so, does it give us a hint about the women in the ship? It's hard to believe so much effort went into making a tapestry of men being hung simply because it was thought to be something pretty to hang on a wall.

The hung men immediately suggest Odin, the god who sacrificed Himself to Himself by hanging from the World Tree. Sacrifices were offered to Odin by hanging.

But those three female figures standing by… Priestesses? Goddesses? The Norns, or Norse Fates?

The Uppsala sacrifices were held in honour of the female powers, the Disir, and the Goddess Freya was the first of them. She is usually represented as a gentle, loving woman, but She had Her fiercer side: She is said to have 'shared the slain with Odin.' Were the women in the ship worshippers of Freya rather than Odin?

There are suggestions of it. One of the carts from the ship is carved with cats, which were associated with Freya - her cart was drawn by them. (A means of transport only available to a Goddess: imagine trying to drive a team of cats.)

The great bed is adorned by horses' heads, and horses were sacred to Frey. Horse fights were held in his honour. Are the horses' heads a reference to Frey and His powers of fertility?

Other historians have pointed to the number of things in the grave carved with serpents, which associate them with the Midgarth Serpent who coils around the earth, and with the giants. The Midgarth Serpent was one of the children of the god Loki and a giantess. Giants were worshipped in the Viking Age. Jord, or Mother Earth, was a giantess, and the mother of the God Thor.

Such Earth goddesses were linked with death and the Underworld, as well as with life and birth.

And what of those cannabis seeds? Nothing in the ship was made of hemp. It's been suggested that the seeds were in the pouch simply because they were rare in the North, and therefore precious. In view of the age-old use of cannabis to produce altered states of mind, I find this hard to believe.

It's known from the sagas that the Nordic witches, or priestesses, practiced a kind of shamanism called seidr, (pronounced something like 'say-th,') which involved trance states. It's known that they travelled from place to place, as a modern preacher might travel around his or her parish. And the practice of seidr seems to have involved a certain sexual fluidity. The gods most associated with it, Odin and Loki, both spend time as women. Loki goes so far as to give birth.

The ship-burial in itself may be significant. The easiest way to travel about Norway, even now, is up the coast by ship, so a travelling priestess might well need a ship.

Ship burials are themselves rare; and it’s even more unusual to find a woman buried in a ship. Grave goods are usually indicative of the gender of the person buried with them: weapons with a man; jewellery and a woman’s tools with a woman. In the Oseberg, the goods are much less specific: as if the grave’s inhabitants had somehow, in life, escaped such clear-cut definitions of gender.

And the older woman, if we believe the theory, had a masculine appearance and a beard.

Anne Stine Ingstad, the respected archeologist who excavated Viking settlements in Newfoundland, suggested that the younger woman may have been honoured, during life, as an incarnation of the Goddess Freya, while the other was a priestess who chose to follow her Goddess into death.

It's possible that, once the great mound was raised over the ship, the mound itself served as a place of worship: Oseberg, the Gods' Mound. And it’s possible that the mound was raised in honour of a woman who was both queen and priestess. The sagas mention royal women who were priestesses.

I’ve always been interested in the Oseberg, but researching this blog has set an insistent vision playing in my head: the ship sailing on dark currents into the earth, into the Underworld. Have its passengers, lying side by side on their great bed, reached their destination yet?

![]() |

| The Oseberg when first excavated |

Susan Price is the Carnegie-winning author of The Ghost Drum. Her book, Overheard In A Graveyard includes a short story, 'Overheard In A Museum' inspired by a visit to Oslo's Viking Ship Museum. The ship in the story, however, is the Gokstad, not the Oseberg.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_VIEWS_OF_GODS_IN_CHINESE_JOSS_HOUSE_pg291.jpg)