|

| Witch Child - illustrator: Nola Edwards |

This year, I received an early Christmas present in the form of an e mail that came through my web site www.celiarees.com. It was from Kate Hebert at the American Museum, Bath http://americanmuseum.org

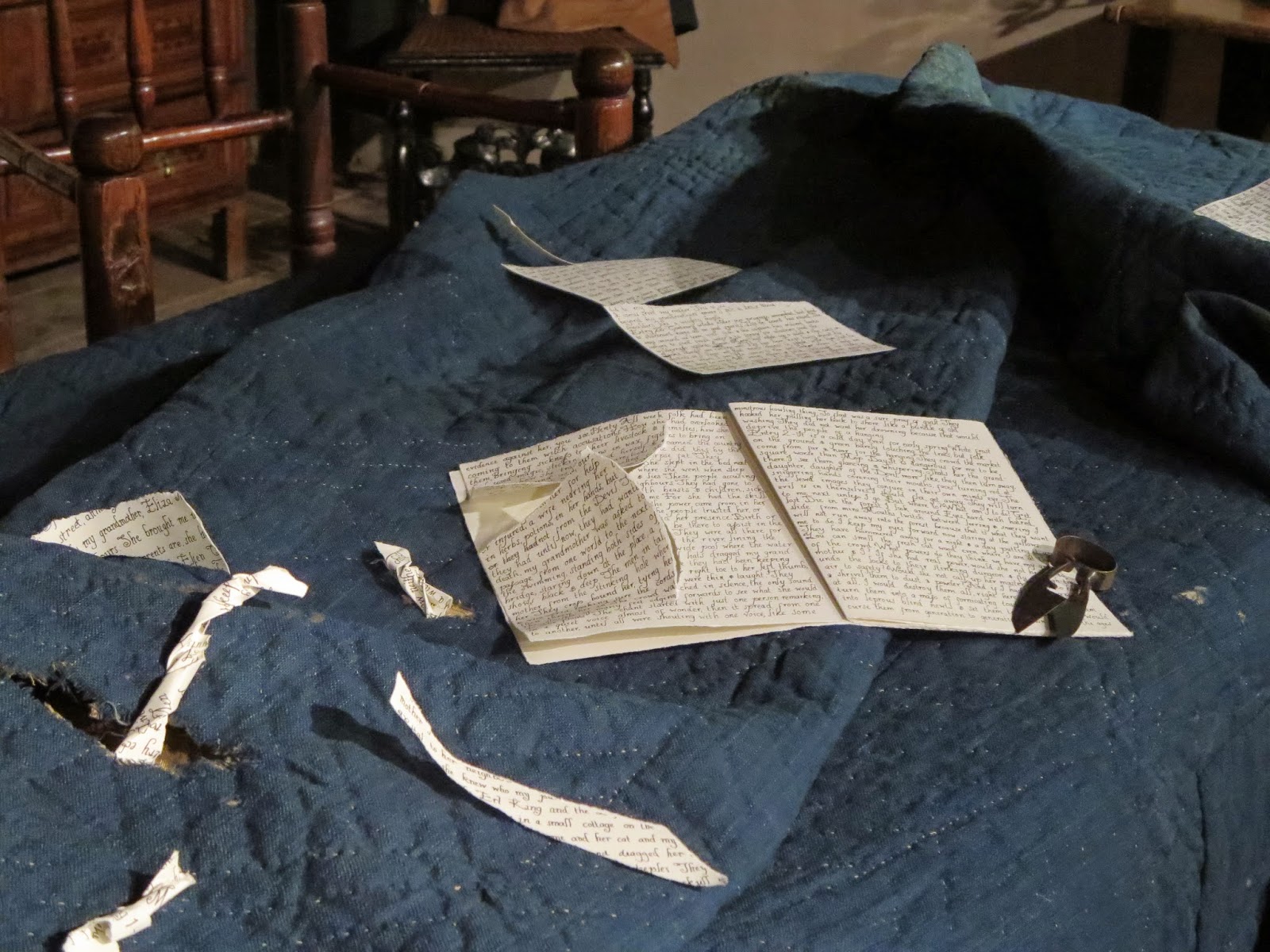

Inquiry: Dear Celia, I am the Collections Manager at the American Museum in Britain. One of my jobs here is to install the Christmas displays. This year's displays are inspired by books and poems set in America. Our earliest room - a C17th keeping room - will be redisplayed to represent the scene from Witch Child where Mary is hiding her diary in the quilt.

One of the very best things about being a writer is getting something like this right out of the blue. I was, of course, delighted and honoured that the museum would think of using my book as part of their Christmas Display, but my happiness went deeper than that because a visit to the American Museum had been central to the writing of Witch Child.

I first had the idea for the book quite a while before I actually got to write it. The idea came all of a piece. I knew straight away that the book would be about a girl who was a witch (or so some would call her), she would be caught up in the last great flaring of witch persecution brought on by the English Civil War and she would escape and find refuge with a group of settlers sailing for New England but she would not be safe, even there, perhaps especially not there...

The ideas came, thick and fast, but I was immediately presented with a dilemma: how to tell the story when at the time (late 1990s) historical fiction was not seen as a popular genre for young adults. To get round this, I decided to write the book as a diary, beginning I am Mary, I am a witch. The diary form would bind the modern reader in and (I hoped) answer publishers' concerns about 'historical fiction speaking to a modern reader' etc. etc.

Once I'd thought of that, other doubts began to set in, as they frequently do. This was obviously going to be a historical novel, mostly set in America but:

a) I hadn't written in this genre.

b) I had only been to America once, ten years before. The trip had been to New England but I hadn't even started writing then let alone thought of writing a book set there in the 17th Century.

c) I couldn't afford to go now.

Behind these concerns was another, deeper, problem. If I wrote the book as a diary, beginning the way it did, what if someone found it? I wasn't prepared to change the first line, or what followed, so I'd have to find some place to hide the diary.

I decided to worry about that later. How hard could it be to write a historical novel? There were books. I had studied History at Warwick University. I realised that the very first spark of the story I now wanted to tell had started in a seminar there. I was working as a part time tutor, so I had lending rights and Warwick has an excellent American collection. I went to the library there, to begin my research, to find out if the story I want to tell was possible. But you can only get so much from books. I needed to get some sense of the physical world I was trying to create. The nearest I could get to going to America was to visit the American Museum outside Bath. So that's what I did next.

I walked through the Period Rooms, lingering in the first one in particular, the 17th Century Keeping Room, making notes, hoping it would speak to me. I took what I could, then I went to look at the rest of the museum. I was wandering through the Textile Room. I was interested in quilts anyway, for their beauty and ingenuity and as examples of women's art, women's creativity. One of the boards caught my attention. I read that quilts from the earliest period were often stuffed with rags and PAPER! I stood, transfixed. That was it. Mary would hide her diary inside a quilt! It was one of those rare moments, of serendipity, synchronicity, it's hard to find the right word, but it brings up the hairs on the back of your neck, it's the moment you know that the book is meant to be.

I bought the book in the bookshop. I did my research. It could work! So that is what Mary did. She hid her diary inside a quilt. The book was written and published in 2000. It was an important book for me. It went on to do very well, to be translated into many different languages, to be read in schools, but I owe its life and therefore its success to that visit to the American Museum.

I bought the book in the bookshop. I did my research. It could work! So that is what Mary did. She hid her diary inside a quilt. The book was written and published in 2000. It was an important book for me. It went on to do very well, to be translated into many different languages, to be read in schools, but I owe its life and therefore its success to that visit to the American Museum. | American Museum, Bath |

|

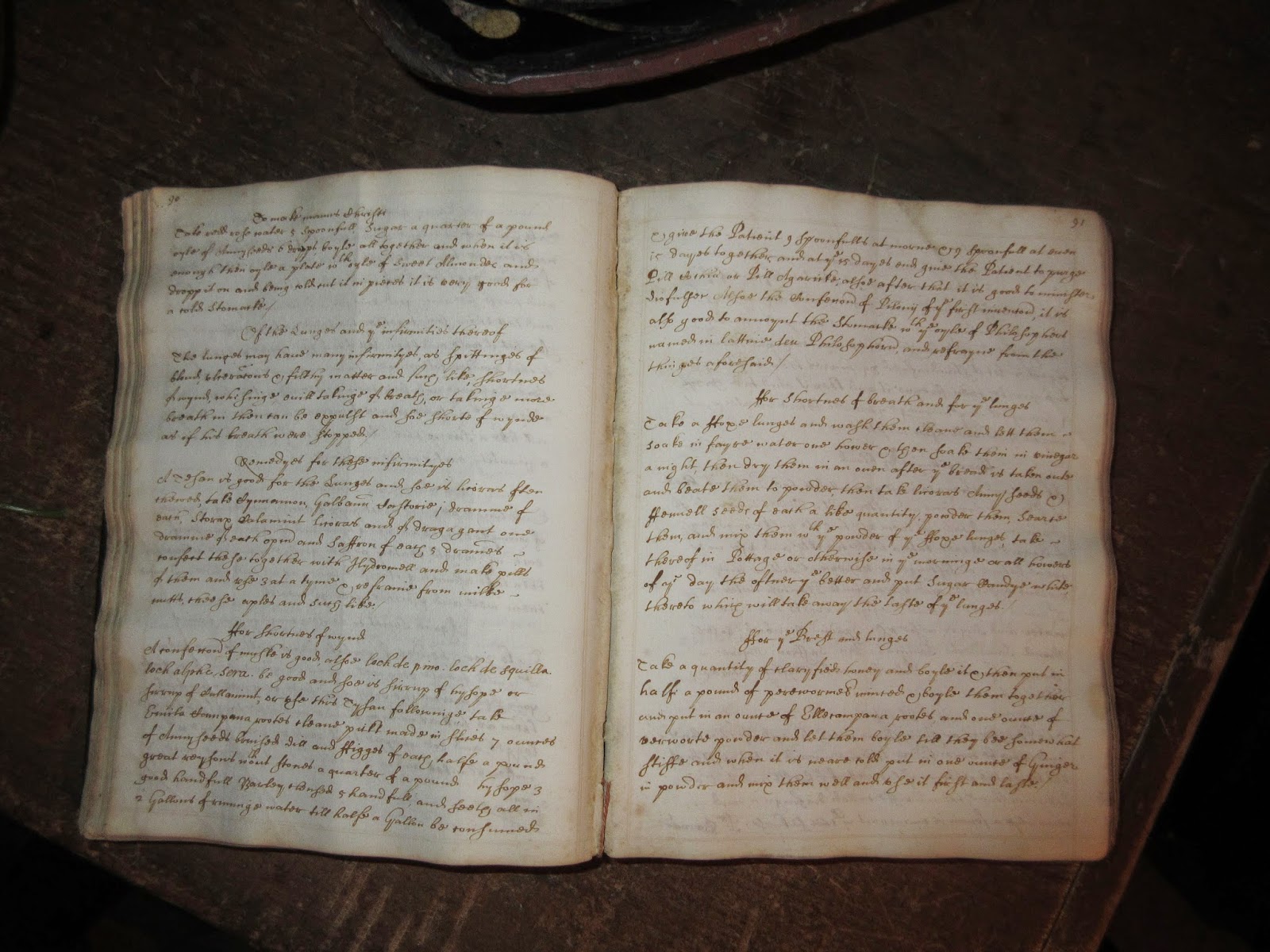

| Herbal Remedies - American Museum, Bath |

|

| Herbal Remedies - American Museum, Bath |

|

| Stitch and Write - American Museum, Bath |

| Keeping Room - American Museum, Bath |

| Keeping Room - American Museum, Bath |

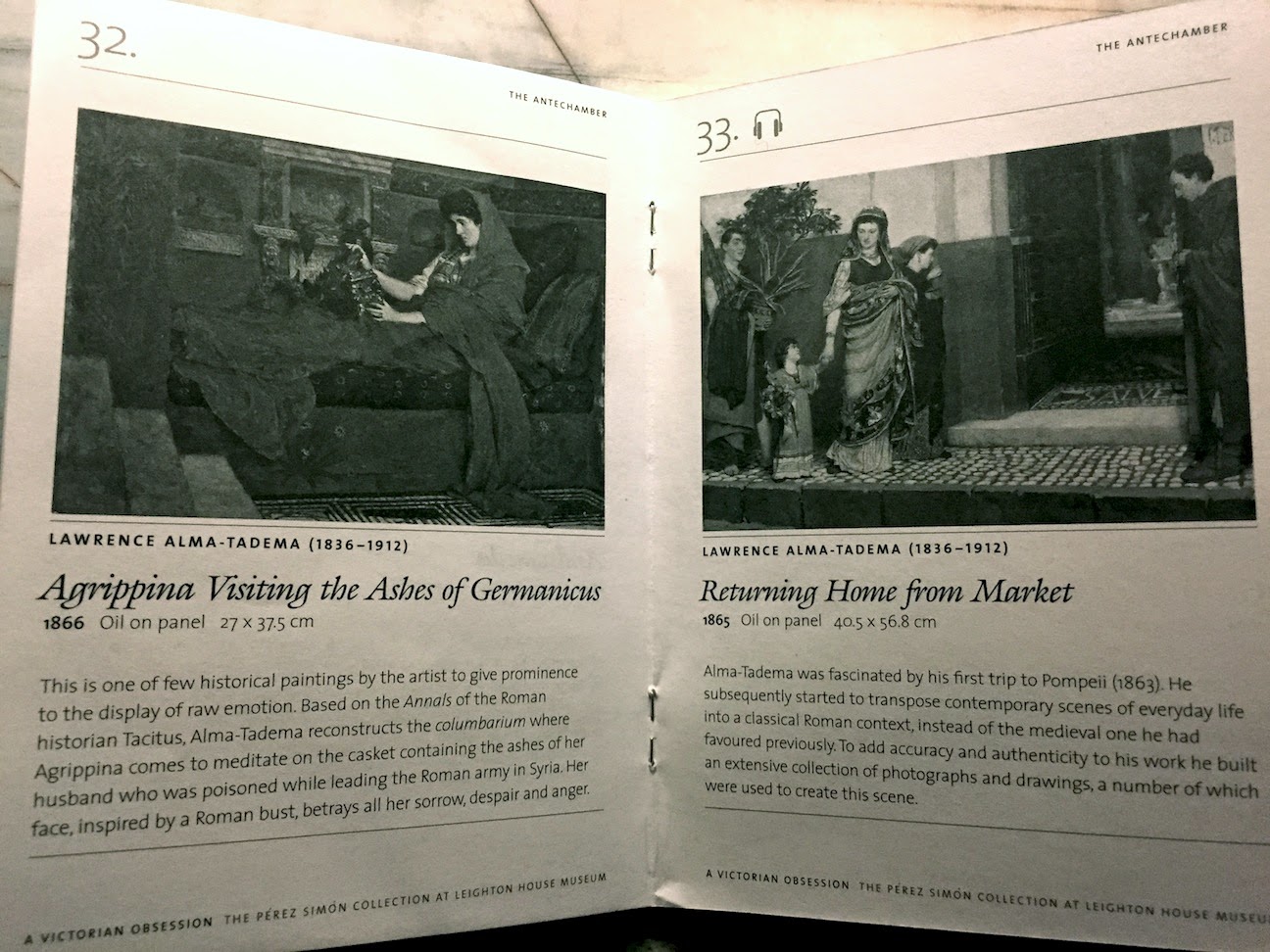

All the Period Rooms in the museum have been lovingly and painstakingly re-created with scenes from popular fiction set in America. Witch Child is in the most wonderful company: James Fenimore Cooper's Last of the Mohicans, Longfellow's Paul Revere's Ride, Washington Irving's Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn, Tracy Chevalier's The Last Runaway, Ralph Waldo Emerson's The Snow-Storm and Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind all have a particular room. The tableaux make the rooms come alive and give life to the books. The contents of each room, the clothes, the quilts, the furniture, the weapons, the books feel as though they are there not just as artifacts from the collection but ready to be used by a character just about to come into the room. Tracy Chevalier said that this made her feel the luckiest writer ever. That makes two of us.

| Scarlett's room at Tara, green velvet dress in the ribboned box - American Museum, Bath. |

Christmas 2014 – A Winter’s Tale is on at the American Museum, Bath.

22nd November - 14th December

http://americanmuseum.org

|

| Sleepy Hollow - illust. Nola Edwards |

Celia Rees

www.celiarees.com

.jpg)

.jpg)