Caveau de la Huchette

![]()

![]()

Sidney Bechet in 1922

What is in a street?

It was my husband, Michel's, birthday last week. We were in Paris. I decided that aside from taking him for a delicious dinner it was time for us to stay up late and go to a jazz club. We haven't done that in a while. Instead of choosing one of the spots we have visited in the past I thought I would find somewhere unknown to us both and after trawling through the pages of

Pariscope ( a Parisian equivalent of Time Out, sort of), I settled on the Caveau de la Huchette which promised good jazz and dancing. Because I was busy I did not take the time to find out the history of the place. I looked up the Californian clarinetist, Dan Levinson, who was billed to play, but nothing about the building itself, housed at 5, rue de la Huchette, a small cobbled street running westward from Rue St Jacques, and a very short walk from Shakespeare & Co. Quintessential Paris

cinquième, steps from where Michel and I first lived when we began our love affair some years ago in Paris. (And where several chapters of

THE FORGOTTEN SUMMER are set).

Rue de la Huchette, Paris 1900

The street itself is one of the oldest along the capital's Left Bank, running horizontal to the Seine and it claims some rather handsome buildings, once hotels. I did not know the meaning of the word

huchette and neither did Michel. So, I looked it up in my four-volume Harrap's dictionary. The closest I found was

huchet, a masculine noun meaning a hunting horn. I then read on Wikipedia that as early as the year 1200 the street was known as rue de Laas and ran adjacent to a vineyard which was sold off in the early thirteenth century for urban development. I have failed to find out anything further about the vineyard, or the wines grown there. If anyone reading this knows more, I would be fascinated to hear from you.

Rue de la Huchette, around 1900

When we lived around the corner from Rue de la Huchette, I have to admit I always hurried by this narrow street, avoiding it when possible, because I found it rather touristy, full of slightly tacky Greek restaurants touting for clients. I have never really taken to its ambience. I now discover that as early as the seventeenth century, the street was lively with taverns, hostelries, cabarets and rotisseries and that the cries and drunken shouts of laughter could be heard all over the quarter! It is claimed that Abbé Prévost (novelist and Benedictine monk) penned his short novel,

Manon Lescaut, published in 1745, in one of these auberges. One wonders with such noise going on how he managed it!

The novel was a huge success and three operatic adaptations were made of the Abbé's

oeuvre. The first, the least known, was Daniel Auber's published in 1856. In 1884, Massenet wrote his opera,

Manon. Shortly after, Puccini adapted the book keeping the original title. This he wrote between 1890 and 1893.

There has also been at least one film adaptation of the book.

Théâtre de la Huchette

At number 23 stands the Théâtre de la Huchette. What is remarkable about this small theatre is that it has been staging the same two Eugène Ionesco plays, performed as a double bill, with the original production values and sets, since 1957:

La Cantatrice Chauve (The Bald Soprano) and

La Leçon (The Lesson). This makes these two plays, as a double bill, the longest running show in the history of modern theatre. Also astounding is the fact that the theatre seats a modest 85 and yet over one and a half million spectators have seen the double bill. Now, a third play has been added to the repertoire, but this changes from time to time. Why, I asked myself, would the same two plays continue to be performed? This story is also fascinating. The theatre opened on the 26th April 1948, founded on a shoestring by Marcel Pinard and Georges Vitaly. In 1952, it was bought outright by Pinard who brought to its stage the works of Genet, Lorca, Ionesco, Turgenev amongst others. Some of whom, like Ionesco, were criticised, spurned by the mainstream theatrical community. When Pinard died in 1975, the theatre was threatened with closure, so the actors who were performing the two Ionesco plays formed a limited company in order that they could continue with the production and fight for the principle's that had been the life-blood of the theatre.

Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jean-Paul Belmondo are but two of a long list of actors who made their first or early appearances there.

Outside Le Caveau de la Huchette 1949

Now to 5, Le Caveau de la Huchette. The jazz club exists in a sixteenth-century building, formerly a hotel, where the American journalist, and author, Elliot Paul, resided during the 20s and 30s. Paul left Paris in the thirties due to ill health and went to convalesce in Spain but moved back to Paris at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. When WWII was declared, he returned home to the States. Once back in America, he went to work in Hollywood. One of Paul's most notable co-screenwriting achievements is the classic

Rhapsody in Blue. (Clifford Odets was another contributor to this screenplay though uncredited)

Original poster for Rhapsody in Blue

Released in New York on 26 June 1945 and nominated for one of the Grand Prizes at the Cannes Film Festival in September 1946

Poster for the first Cannes Film Festival held in September 1946

Back to Rue de la Huchette. No 5 is built of stone with a cavernous dungeon-like interior with dangerously narrow winding stairways that lead to two seating areas. The largest 'room' is the underground dance floor and stage where Dan Levinson was playing.

Caveau de la Huchette started its life as a jazz club in 1946 and today is hailed as the Temple of Swing.

But looking back centuries earlier into the history of No. 5, I discovered that it was a meeting place for the secret brotherhood of the Rosicrucians and also for the Templars. The history is a little woolly after that, but it seems that in the early seventeenth century, the building was used by a Brotherhood of Freemasons. (Freemasonry was founded from "ecclesiastical associations of builders formed by bishops from the Middle Ages, especially the Benedictines, Cistercian and Templars" so perhaps the use of the space was passed down from the Templars?)

The lodge was composed of two basement rooms, one on top of the other, which served as the meeting rooms. From these rooms, two subterranean tunnels were excavated. One led to Châtelet and the other to the cloister of Saint-Severin.

(This is not as incredible as it sounds. Paris is built on old holes, quarries, catacombs and subterranean trails. As Victor Hugo wrote, "to plumb the depths of this ruin seems impossible".)

Georges Danton Lawyer and Politician 1759 - 1794

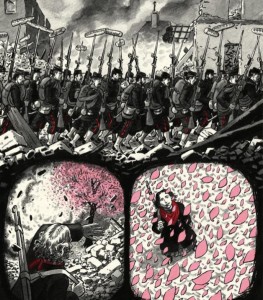

During the years of the French Revolution, No. 5 became an important gathering point for radical democrats seeking to dislodge the monarchy and create a republic. It hosted members of the Club of the Cordeliers. The upper room was transformed into a public house where such political luminaries as Danton, Marat and Robespierre came to drink and sing revolutionary songs, songs of La Liberté. Trials and executions took place in the lower room. A very deep well still exists there which is claimed to be where the corpses of those executed were thrown. Arms from that epoch still decorate the walls.

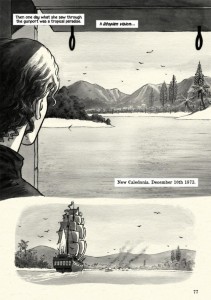

In 1946, Paris was a capital celebrating its freedom, a different liberty. The Germans had gone, the Occupation was at an end. The Americans were back. Everybody was in the mood to party. Jazz and its upbeat energy swept through Paris. The Caveau de la Huchette claims to be Paris' first jazz club but I would contest this because Sidney Bechet, to name just one, was playing with his own band in 1928 at the the chic nightclub, Bricktop's Club in Montmartre, owned by flaming red-haired, "one-hundred percent American negro", Ada 'Bricktop' Smith.

The Caveau certainly welcomed the GIs and with them came the beginning of France's passion for be-pop and swing. It was nicknamed the Temple of New Orleans jazz.

Sydney Bechet's jam sessions down in those cellars after his return to France in 1950 have become legendary.

Sidney Bechet 1897 - 1959

The club's reputation has never faded. Lionel Hampton performed there for the club's thirtieth birthday celebrations in May 1976.

Every night of the week there is live jazz, and, what was an eye opener to Michel and me, was the dancing. Be-pop and swing are alive and jumping in Paris. Dozens of couples, singles too, congregate there to dance. It was a remarkable sight to see and you cannot help feel energised and uplifted. Dan Levinson, in from California to play for two nights, said that it is one of his favourite clubs to perform anywhere in the world. No musician could claim that the reception was anything less than '

très chalereux'.My new novel - the one I am at work on now - its title for the moment, though for a very different reason, is

All that Jazz (though I am sure Penguin will have other suggestions!) It begins in Paris in 1947. I feel very tempted now to write a scene set at the Caveau de la Huchette.

Here, below, is the cover of THE FORGOTTEN SUMMER, also partially set in Paris, published a couple of months ago.

www.caroldrinkwater.com