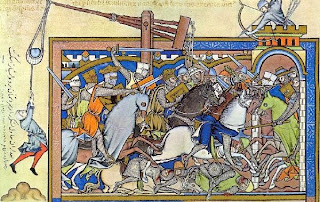

When writers mention conflict they are often talking about a tension between two or more of their characters. However, when Harrogate History Festival hosted a panel on this theme, conflict meant “battle and action and weapons”.

When writers mention conflict they are often talking about a tension between two or more of their characters. However, when Harrogate History Festival hosted a panel on this theme, conflict meant “battle and action and weapons”. The panel was chaired by John Henry Clay, whose interest is late Roman history and the three speakers were A.L.Berridge, who has written here on the History Girls about the Crimean war, Robyn Young, who created a weighty trilogy on the Crusades, and the Viking author Rob Low. The following post is based on my notes of the session.

JHC: Conflict scenes can be the most difficult scenes to write, and to get right. Of all the “living in the past” historical experiences the writer might identify with, being in the middle of a battle is the possible hardest to understand.

JHC: Conflict scenes can be the most difficult scenes to write, and to get right. Of all the “living in the past” historical experiences the writer might identify with, being in the middle of a battle is the possible hardest to understand. Not only does the writer have to meet their reader’s expectations, the battle scenes have to fit into the full story and be read as part of the characters life or lives but battles are, by their very nature, incredibly complex events.

So, what makes a good battle scene?

ALB: Jeopardy! The character has to have something at stake. There must be turning points. Even when the historical outcome is known, the scenes can’t be predictable. You need variety, but there’s more variety in some conflicts than in others. For example, the Battle of Inkerman took place in thick fog, which doesn’t offer a great range of opportunities, but the Battle of Balaclava contains many different elements.

ROB: You need variety to for yourself as a writer, too. Battle scenes can be hard and exhausting to write, especially if you are working on a long book. It helps if the battle setting offers a variety of terrain, or landscape. Variety of action too: you have to find new ways to kill people and make use of when and where the fight takes place and the range of weaponry. Is it arm-to-arm fighting in mediaeval alleyways, a campaign across deserts and plains, or a battle set in the Scottish highlands? It can be hard to maintain suspense if the reader knows what happens to certain characters.

LOW: There’s also the change that happens within a battle. For example, Robert the Bruce began the battle with a full range of armour and accoutrements, riding a fine horse, with pennants flying around him. By the end, he was on the ground, fighting with barely the shirt on his back. I’d say that terrain is everything in a battle. Are you fighting from high to low ground? Is there a water or marsh behind you? Is there a bridge? Are you on horse or foot? At Bannockburn, the English cavalry were falling on the infantry, who were trying to escape across a bridge of trampled flesh.

ROB. In a funny way, sex scenes and battle scenes are both hard to write. Everyone “knows” what’s done, but it is everything that the individuals bring to the scene that make it interesting.

LOW: Another thing I’ve learned, even through battle re-enactments, is that time within battle works in an odd way. It is mostly hours of faffing around followed by a few minutes of sheer, absolute terror and one-on-one experiences. There’s also the variety of people involved. Remember, for centuries it was always the “wee guys” who did all the fighting for the “big guys. The wee men did not have the big plan. They just fought as best they could, hoping that everyone else around them was doing their job.

LOW: Another thing I’ve learned, even through battle re-enactments, is that time within battle works in an odd way. It is mostly hours of faffing around followed by a few minutes of sheer, absolute terror and one-on-one experiences. There’s also the variety of people involved. Remember, for centuries it was always the “wee guys” who did all the fighting for the “big guys. The wee men did not have the big plan. They just fought as best they could, hoping that everyone else around them was doing their job.JHC: Is it necessary to keep the reader informed of the wider view of battle and if so, how?

ROB. It depends on what you want to achieve. For example, when I was writing about the Crusades, I wanted to show the panorama of the landscape and the larger scale action.

ALB. One advantage in writing about the Charge of the Light Brigade is that information could be held back: from the point of view of those first in the Charge, they did not know they were heading for defeat. They did not know Lord Lucan had turned back.

ALB. One advantage in writing about the Charge of the Light Brigade is that information could be held back: from the point of view of those first in the Charge, they did not know they were heading for defeat. They did not know Lord Lucan had turned back. Historical writers have to take care with fairly recent history. Readers can be very knowledgeable and sensitive about the regiments and reputations involved in a battle so get the facts of the action correct. One way of dealing with this complexity is to show the battle from several different character’s points of view, including enemy action. This does mean that you have to plan out the writing of your battle scenes in advance.

LOW: The climate and seasons and weather will affect your battle setting too, not just the location on the map. If you visit Bannockburn at Midsummer, the ground can be rock hard, crossed by little streams here and there, not a bog or marsh.

JHC: Is the documentation of battles a blessing or a curse? Before the Crimea, “documentation” usually meant the general’s formal reports. Since the Crimean war, there have been newspaper articles as well as many accounts by ordinary people.

ALB: There are so many wonderful accounts, but the downside is that many or so very, very literate, bringing you the sounds and the smells. As a write you can’t improve on that, so the only way is to go for another man’s experience.

LOW: Accounts get changed and re-written. Back in time, there were the Viking sagas. Originally they were the fragments of tales for telling around the fire. Then a collector nailed them together in an often-incoherent way. Even so, such accounts are invaluable as a way of understanding the ethos of the period and discovering how people thought and lived and died.

For example, Vikings didn’t think of wanting battles. They just thought of killing people. Besides, the details are important. You have to remember that you’re writing for people who may not know the historical details. (People who believe “Braveheart” to be history, for example! Much laughter.) If you look at the accounts of the numbers who died, often the wee man aren’t recorded, only the aristocrats. You have to be careful of tradition too, and think of the audiences that “historical” writers and novelists were writing for, and why they were writing.

JHC: Thinking about the writing of your characters, do you think fighters in the past suffered the same traumas that we hear soldiers suffering today?

ROB: I’d heard my granddad’s war stories about all the ordinary difficulties and illnesses. Then, for the Brethren novels, I talked to a lot of people, both military and medical. Besides, the mind-set in the past was probably very different. Ordinary people did not matter. They fought when the call from their lord came and, if they survived, went home back to their farms. The valuable people were those with riches and property, because they could be offered for ransom. The first time that we hear of nobles fighting in battle was in the Second Barons War in the Vale of Evesham when Prince Edward wept because the battlefield was “covered in bloody red ribbons” of all the gentry he knew.

ALB: The attitudes of the past and present don’t always match. Religion was very important to people’s lives and culture in the past, in the17th Century. Peasant’s lives were always difficult and harsh. They faced death in so many ways already: disease, injury, starvation, lawlessness and, for women, childbirth. If daily life has such a high death rate, dying in battle might not seem so terrible.

LOW: In some societies and times, the acceptance of death was almost a cult. A Viking would be ashamed to die in his own bed. His greatest fear would not be death, but the fear of not being brave, of letting his brother warriors down, an attitude that still exists as part of today’s squaddie culture.

JHC: What do you feel about the amount of gore needed to write battle scenes?

ALB: In some ways, “gore” is voyeurish: blood and injuries seen by the onlooker not the participant. When you are in action in the middle of a battle, you don’t register such things the same way. You are too busy worrying about what’s happening next. However, the soldiers involved in the Charge of the Light Brigade were also spectators, because they were charging at cannons. They did see heads blown off, horses running with dreadful injuries, their friends blown apart. The carnage was visible. The survivors, retreating, saw the vultures already gathering on the bodies of their dead comrades.

ROB: You do a disservice to your readers if you don’t give them a realistic idea of what the battle was like.

Finally, a couple of the questions from the audience:

How do you approach trying to convey sounds in battle?

ROB: Re-enactment helps. You need to hear the difference between the sounds. How does a pistol sound? Or a musket? There’s also all the other sound, such as bugle calls or drums.

ALB: First hand accounts help. Two genuine writers were at the Crimea, and they recorded the details a sthey . One Captain wrote about the terrible “slosh” of the cannonball when it hits a human body.

ROB: It’s useful to take part in or attend re-enactments. For example, chain-mail does not rattle, it “shushes”. (LOW demonstrates with a handy tunic)

LOW: But in the middle of a battle or fight, your ears may be covered by a metal helmet so you hear your own breath and not much else. (LOW demonstrates with three handy helmets, one with no ear-gap, one with, and one with hinged ear flaps.) ou might pick up bugle calls but you can’t hear commands. You see the standards and rally towards them.

How do you draw the line between creating a hero and the horror of war?

ALB: You have to remember that the antihero and the villain are aspects of the hero.

ROB: Also, you can’t judge a “hero” by modern sensibilities. You need to find the areas where the hero and the reader connect.

LOW: Heroes are accretions of other people’s dreams and hopes. For example, the hero Robert the Bruce was a ruthless, cunning and mean s-o-b, but he was better at it than most of the others at that time. A hero is a symbol, a figurehead. He is a human being whose side you can be on. Their task is to do other things and survive.

ALB. When you write, you try to show both the good and bad aspects of ordinary human people. In my opinion, Cardigan and Lucan are the villains of the piece.

Conflict in Fiction was a totally fascinating session, so thank you to all the speakers quoted here, and apologies for any errors in my note-taking or attribution.

The first Harrogate History Festival was supported by several history publishers and planned with the help of the Historical Writers Association. I’m fortunate in living quite close to The Old Swan Hotel so, while I couldn’t attend the whole weekend, I was able to drop in and out of sessions and talks. I’m already watching out for next year and may be offering my notes on a couple of other talks here on History Girls over the next month or so.

Penny Dolan