A bit about Celia:

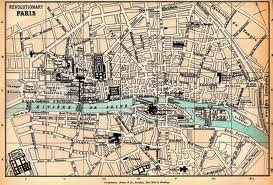

Celia Brayfield’s first novel, which began in Malaysia in 1938, was written when historical fiction was the love that dared not speak its name. She subsequently smuggled revolutionary St Petersburg, Paris with the Ballets Russes and the Barbary Coast in the eighteenth Century into some of her nine bestselling novels. Her next novel is about the love affair between a French man and an English woman that finally brought Mary Queen of Scots to justice; in retelling this tragic episode in English history, she has used recent research to follow the lives the ordinary people trapped Mary’s doomed court-in-exile. Celia also tutors award-winning students on two of Britain’s leading Creative Writing programmes, at Bath Spa University and Brunel University in London. She is the author of Bestseller (Fourth Estate) 1996, one of the very few guides to writing successful popular fiction from a bestselling author.

She is also the guest editor of the winter 2013 edition of Mslexia.

Here she muses on why anachronistic attitudes to love and sex have sometimes given historical fiction a bad name.

Bodice-ripper. Shall we just think about this for a moment? Yes, it’s publishing slang for popular historical fiction for women and it tells us about the mindset, fixed in the Mad Men era, that put historical writing beyond the literary pale for decades. Bodice-ripper believers are sure that that our ancestors were randy as stoats, at it like crazed weasels and permanently breathless with passion.

I think not. The eminent historian Lawrence Stone thought not, in his tome The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 (1977) which transformed thinking about relationships in the early modern period and in which observed that people had far less sex at that time than we imagined they did.

Likewise with love. History certainly offers us epic romances – the love of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, which endured thirty years and his first two highly advantageous marriages to other women, or the coup de foudre which led Eleanor of Aquitaine to dump the King of France for the unprepossessing Duke of Normandy – later Henry II of England. But the writer who tries to tread a path between accurate history and engaging fiction is confronted by the fact that neither love nor sex have meant the same to our ancestors as they do to us today.

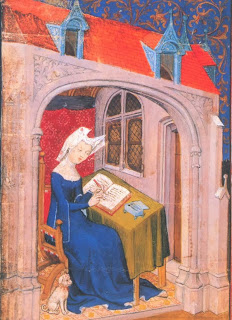

Worse, we have very little evidence to tell us how ordinary people felt, thought and acted about love, and what we do have – the poetry, the erotica, the court testimonies – was not created to provide a record, but to serve a purpose at the time. Finally, worst of all, many authors have made considerable fortunes by ignoring these facts and having Tudor noblewomen act like Essex girls.

Love is the stuff of fiction, particularly popular fiction, but love has not always been the intense, intimate and sexual emotion we recognise today nor was it always considered the best foundation for a marriage and family. History is not on the writer’s side. Mostly, love has been an anarchic challenge to the social order.

Love and the novel have a shared history. Romantic love was defined by the romantic movement of the late eighteenth century, in which the idea that emotions should be all-powerful and should triumph over reason was central. The novel itself emerged at the same time and their linguistic origins are intertwined, with the word romance having double meaning – a love affair or a story. The sociologist Anthony Giddens has suggested that romantic love introduced the idea of a narrative into an individual's life and reinforced the link between self-realisation and freedom.

It is ironic that the period of English history that is currently such a focus of fiction was one of the least romantic. To modern readers, the true Tudor attitudes to love and marriage e are depressingly pragmatic. The immense dynastic marriages of the time, such as that of the Earl of Shrewsbury and Bess of Hardwick, a three-couple alliance which included four of the couple’s adult children, seem cruel and incomprehensible to us.

Equally hard to understand is the story of Lady Catherine Gray, heir to the English throne, who fell in love and married Edward Seymour, the Earl of Pembroke, in secret while negotiations for a diplomatic alliance for her were under way. Within months Catherine’s young husband was sent abroad and his sister, the only witness to their marriage, died. Catherine lost the legal document that proved their marriage, and the priest who married them disappeared. She found herself pregnant, with a child that was, to all intents and purposes, illegitimate. Queen Elizabeth suspected a plot and Catherine was imprisoned for the rest of her life. To modern readers, and to fine novelists including Alison Weir and Ella March Chase, this is a tragic story of true love. To an Elizabethan audience, this is a tragic story of an unbelievably silly and disloyal young couple. And to male historians, alas, it has been proof that Queen Elizabeth was an embittered spinster.

Does it matter that a novelist in pursuit of more readers makes a Tudor lady act like an Essex girl? To me, yes. Surely the reason we explore the past is to find out what human nature really is. If we traduce our ancestors’ feelings, there’s no reason to get to know them at all. And besides, a bodice meant exquisite fabric imported from far-off lands, jewels, gold thread, skilled embroiderers, weeks of work for dozens of people – the man who ripped it wouldn’t be anyone’s favourite.

Extracted from Writing Historical Fiction:The Writers’ and Artists’ Companion, by Celia Brayfield and Duncan Sprott, published by Bloomsbury Academic, December 5 2013.

.jpg)