We used to have my grandparents over for Christmas Day. I didn’t realize my grandfather was nearly blind or that his deafness dated from the Somme, and can only remember the frustration of watching ‘The Towering Inferno’ while he sat four inches from the screen and turned round after an hour to ask in a hoarse whisper, ‘Is there a fire?’

Yes, I hate myself now. But it wasn’t only my grandparents’ own history that I missed, and I was always puzzled when at the end of the meal my grandfather would raise his glass and make a solemn toast to ‘Absent Friends.’ The gravity whizzed straight over my childish head, and it was many years before I realized we weren’t just drinking to family in Canada for Christmas, but to people who were actually dead.

But there's more to this than any one individual's recollections. Ritual is a repetition of acts performed in the same way over the long parade of years, and in its performance we are opening the door to history. That the Commons doors should be slammed in Black Rod’s face at the opening of Parliament derives from the 17th century, that the Lord Chancellor should sit on the ‘Woolsack’ goes back to the 14th, and when we see these things done then we’re watching history.

We saw it in July when the board at Buckingham Palace announced the birth of Prince George. We can see it every day – in the lowering of a flag, the wearing of a Judge’s wig, the Changing of the Guard. When a Latin Grace is recited at High Table, when monks chant Plainsong, when a bugler plays the Last Post, then we are hearing it too. And when we take communion, or drop a penny in wishing well, or even say ‘Bless you’ to someone who sneezes, then we’re not re-enacting history, we’re living it for real.

|

| Popular wishing well in Kyoto |

It’s perhaps this last which matters most to historical novelists. It’s true we spend our time recreating worlds profoundly different from our own, but when we want to engage our readers’ emotions then we concentrate most on those things that are the same. Love, death, friendship, betrayal – everyone can identify with these, and empathize with those characters who experience them. I would argue that the same is true of ritual.

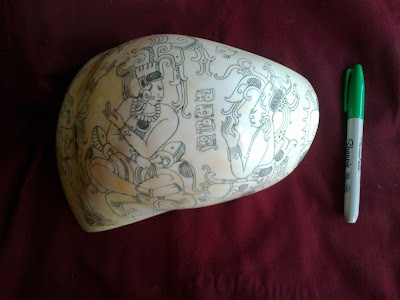

Obviously it’s harder in some periods than others. Not many of us have actually poked about in an animal’s entrails as a means of foretelling the future, and I can’t say I’ve ever made an offering to Athene, but even in the classical civilizations we can still recognize the familiar seeds of actions we perform today.

When someone ‘tempts fate’ by a careless remark I may not say ‘Absit omen!’ and ‘spit in my bosom’, but I might well cry ‘Don’t say that!’ and jump to touch wood. Different actions, but when Robert Graves described a character doing this in ‘I, Claudius’ then the jolt of recognition was just the same.

And as the centuries roll on it gets easier and easier. There are Christian churches where the readings still come from the King James Bible (1611) and the communion service is conducted by the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. There are (secret) places in England where Morris Dancing isn’t a re-enactment, but continuation of a tradition handed down from generation to generation to keep alive the pagan ritual. My own favourite annual Fair is the one at Bampton in Devon, which has been going on even before Henry III granted its Charter in 1258. It’s not a quaint re-enactment like a Victorian ‘Christmas Fayre’, it’s a real county trade-meet which has quite simply never stopped.

|

| The Bampton Mummers at this year's Charter Fair |

Ritual has a way of surviving, particularly when it’s fun. I doubt we’d really bother to ‘Remember, remember the 5th of November’ if it didn’t have fireworks and a bonfire thrown in – but we do, and it’s one of our strongest links to the past. In the Sussex village of Lindfield they even have a Guy dressed like Fawkes himself and the Lindfield Bonfire Society lead it to its doom with 17th century speeches and cries from the crowd of ‘Down with Popery!’

But it’s not just Guy Fawkes we remember now, any more than it’s only Christ we think of at Christmas. The ritual has entered history in its own right, and ‘Bonfire Night’ links us to other centuries simply on the grounds that we have all celebrated the same thing. I remember experiencing a moment’s ‘double-take’ when Sergeant Timothy Gowing in the Crimea wrote of the Battle of Inkerman (5th November 1854) ‘That was keeping up Gunpowder Plot with a vengeance!’

It can even apply beyond the specific event being commemorated. Bonfires and fireworks were around long before Guy Fawkes, but it was my experience of November 5th that made it easy for me to write about them. Describing a display in 1640’s Paris for ‘In the Name of the King’ I had to remember that the fireworks were white rather than coloured, and arranged mainly in static set pieces, but the effect on the crowd was one with which we’re all familiar. They made the same noises of ‘ooh’ and ‘ah’, and my rustic narrator noted with wonder how ‘men with hardened faces and swords on their hips turned suddenly into children.’

|

| From Claude Lorrain's Firework Series (1637) |

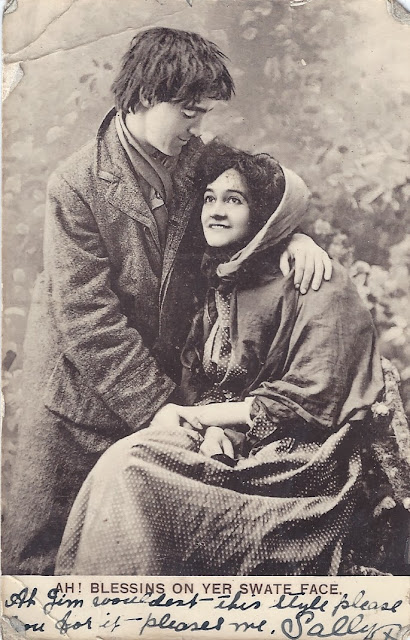

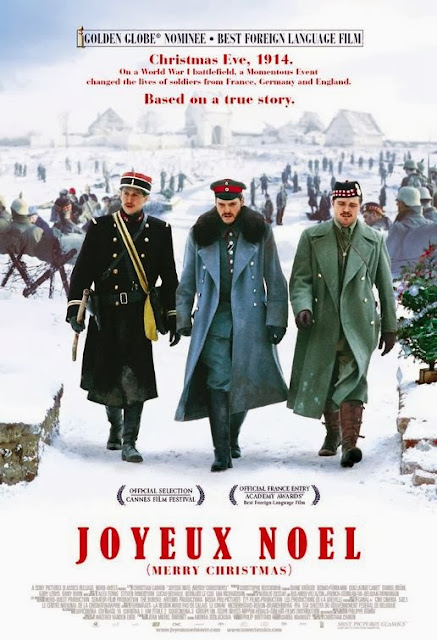

It has the power to touch us like nothing else. This little video of Christmas in 1914 is only two minutes long, but it contains one image that hits me like a kick in the stomach.

For me it’s the hats. The tins of pudding are unfamiliar to me, as alien as the trenches themselves, but those hats are identical to the ones that fall out of crackers at every Christmas table in Britain. Their remembered flimsiness is suddenly so vivid that the jollity becomes unbearable, everything so real and immediate that I want to reach into the screen and grab the men out of it, anything to save them from the horrors that only we know lie ahead.

And Christmas is full of such ambushes, each a little sensory pool of memory to trap the unwary. The glittering decorations, the trees and fluttering candles, the taste of turkey and mulled wine, the smell of cinnamon and mince pies, the tearing of paper, the sound of carol singers, a Salvation Army band, the snap of crackers and the laughter of children. Even (heaven help us) bloody Slade. Memory catches in every particle of it, and the older we get the more we find nothing has been lost. If ritual is the doorway to the past, then on Christmas Day it’s gaping wide open.

And to history too. Mince pies may no longer contain meat – but a recent culinary experiment proved that few could tell the difference between the modern pie and those created by Mrs Rundle 160 years ago. Health-and-safety may have killed the idea of charms in the Christmas pudding, but crackers still contain their substitutes – just as they in turn are the modern equivalent of ‘pulling the wishbone’. It’s true that many of our Christmas traditions date back only as far as the 19th century and Dickens, but some are far, far older, and carols like ‘Good King Wenceslas’ and ‘The Holly and the Ivy’ are mediaeval in origin. The sole surviving manuscript of ‘Adam lay ybounden’ is dated to the fifteen century, and the song itself is believed to be even older. Listen to such things, and you won’t be going back just to your own youth – but to the childhood of Henry Tudor.

|

| Fragment of the surviving MS of 'Adam Lay Ybounden' |

That doesn’t always help when we’re writing about places with their own traditions, but my own favourite Christmas ‘ingredient’ is universal to all the so-called ‘Christian countries’. It’s rarer now, and whether we personally experience it depends entirely on the town or village in which we live, but to me it’s the most magical of sounds, and one that spans the years like no other. In 17th century Paris it would have been uttered most dominantly by the voices of Marie, Jacqueline, Gabrielle, Guillaume, Pasquier, Thibaud and the Sparrows, but the same kind of sound rang out from besieged Sevastopol in 1854, and can be heard today in every city in Europe.

This sound. This. You don’t need to be Christian to appreciate the gladness of this, or to share in the experience that’s been enjoyed across the centuries by rich and poor alike. This is the very sound of history, and if December 25th takes us back down the tide of memory, then in my mind it does so to the sound of Christmas bells.

***

A L Berridge's much less sentimental website is here.

Her shameless appeal to Christmas charity for soldiers without graves is here.

The rest of her is probably somewhere else scoffing mince pies.

.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project+1.jpg)