Nervous eyes on cloudy skies, last month I slid a garden cane into a homemade red flag and set off to Fitzrovia lead my first ever historical walk.

Liberty’s Fire is a novel that could hardly be more firmly set in Paris, but in a sense, Fitzrovia is both where it began and where it ends. I had found my way to the Paris Commune through the chance discovery that my great-great grandmother, Nannie Dryhurst, had worked as a volunteer teacher in the early 1890s at the anarchist International School set up by the legendary Communarde, Louise Michel – more about whom here. And since this part of London was home to several generations of French revolutionaries during the nineteenth century, I don’t think I’m giving too much away to say that it made sense to gather my surviving characters here at the close of the novel. When the Fitzrovia Festivalinvited me to design a walk exploring the fates of Communard exiles in London, I happily agreed – and began to investigate. Here's just a little of what I discovered and the route we took, and since I’m not now extemporising on the move, I can include some references word-for-word rather than summarised from memory…![]() |

Outside the Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre, Tottenham Street,

with some of the walkers before we set off. |

First stop: Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre, Tottenham Street

A little background before I introduce my main characters….French political exiles came to London in several waves. The first were known as the quarante-huitards, who took flight in the wake of the 1848 uprising (vividly – if partially – described in Flaubert’s A Sentimental Education) and a few years later in ’51 after Louis-Napoleon’s coup, when the Second Republic was overthrown and the Second Empire set up. (Sticking with fiction, Zola’s The Belly of Paris/The Fat and the Thinopens with the return of his hero from a penal colony seven years later.) Following the dramatic fall of the Paris Commune in May 1871, and the horrors of ‘Bloody Week’, over three 3,000 took refuge here, and were welcomed and looked after by the rump of the quarante-huitards who remained. Some of course were involved in both revolutions, having returned to Paris in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian war after the defeat of the Emperor and the declaration of the Third Republic. They fled to escape firing squads, prison and transportation to New Caledonia. Most were ordinary working-class Communards in their 20s and 30s, 1200 were children, and some were prominent political leaders like Lissagaray. Wondering why London’s oldest patisserie, Maison Bertaux, was founded in 1871? Wonder no longer. And then followed yet another wave, arriving in dribs and drabs in the decade after the amnesty of 1880. Some, like Louise Michel, had tried going back to France to take up the revolutionary cudgels once more after eight years in the Pacific, and were fed up with constant arrests and imprisonment. They were not necessarily anarchists before the Commune, but many embraced the movement in one form or another afterwards.

Second stop: Newman Passage

Old Fitzrovia lives on in this atmospheric alleyway, pictured here in the illustrated newspaper, The Graphic, (2 February 1972).

![]() |

©The Museum of London

|

Most Communards arrived here with absolutely nothing, lucky to have kept their lives. Many had had nothing to start with, which was why they were prepared to risk everything for the progressive Commune. As Constance Bantman puts it, ‘the comrades tended to the most basic needs of one another’, and as you can see here, this meant feeding minds as well as bodies. This co-operative ‘soup kitchen’ allowed exiles to talk as well as eat, and carried on the principles of collective action and social reform established by Communards like Nathalie Lemel and her fellow Internationalist Eugene Varlin in Paris in 1868 when the Emperor’s restrictions on freedom of association first began to lift a little. Both were bookbinders and trade unionists, and Varlin, one of the most popular delegates on the Commune’s Council, who had opposed the anti-democratic Committee of Public Safety with its echoes of the Terror, fought on the barricades in the 6thand 10th arrondisements during Bloody Week, and tried to stop the controversial execution of the Commune’s hostages. However he was arrested after being recognised by a priest, tortured, and shot, and died with ‘Vive la Commune’ on his lips. In 2007 a small (triangular) square in the Marais, very near the French headquarters of the International Workingmen’s Association was named after Lemel, who is credited with having converted Louise Michel to anarchism while they were both deportees.

![]() |

| Newman Passage |

Third stop: the Autonomie Club, 32 Charlotte Street.

Later exiles found soup and comradeship just round the corner at the Autonomie Club, a forum for international anarchism in London founded by German comrades in 1886. In November that year it held a fundraising evening featuring speeches, song, dancing and a tombola to support a radical newsletter in Bohemia. Later the club moved a few streets away to Windmill Street, and it may have been here that ‘chemistry lessons’ were held…a.k.a. instruction in the making of explosives. The principle of ‘propaganda of the deed’ was beginning to divide the movement. The police continued to raid the premises.

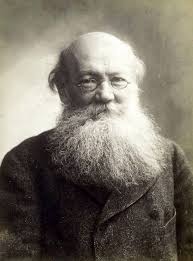

I imagine my great-great grandmother introducing her lover Henry Nevinson to the enticing world of the Autonomie club, as they both escaped unhappy marriages for the combined excitement of politics and romance. In a crowded cellar, full of foreign refugees and English ‘enthusiasts for anarchism’ Nevinson met for the first time the Russian anarchist, Pierre Kropotkin.

“Anarchists do not have a chairman, but when enough of us had assembled a man stood up and began to speak. His pronunciation was queer until one grew accustomed to it (‘own’ rhyed with ‘town’, ‘law’ with ‘low’, and the ‘sluffter field of Urope’ became a kindly joke among us). He began with the sentence, ‘Our first step must be the abolition of all low’. I was a little started. I had no exaggerated devotion to the law, but, as a first step, its abolition seemed rather a bound. Without a pause the speaker continued speaking, with rapidity, but with the difficulties of a foreigner who has to translate rushing thoughts as he goes along…Comrade Kropotkin was then about fifty, but he looked more. He was already bald. His face was battered and crinkled into a kind of softness, perhaps owing to loss of teeth through prison scurvy. His unrestrained and bushy beard was already touched with the white that soon overcame its reddish brown. But eternal youth diffused his speech and stature. His mind was always full gallop, like a horse that sometimes stumbles in its eagerness. Behind his spectacles his grey eyes gleamed with invincible benevolence….He seemed longing to take all mankind to his bosom and keep it warm…” (Fire of Life, page 53)

![]() |

| The 'Anarchist Prince', Kropotkin |

Dryhurst was already a close friend of Kropotkin through the English Anarchist group centred around Charlotte Wilson, founder of the only recently defunct Freedom newspaper; later Dryhurst would translate his book The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Nick Heath’s short biography of Dryhurst includes a description of her own first meeting with Kropotkin at a party given by William Morris. Many readers of this blog will already know that Kropotkin – along with Stepniak – was the model for E. Nesbit’s Russian dissident in The Railway Children. A little later I waved my red flag and reminded my fellow-walkers of Bobbie's red petticoats.

Fourth stop: Conville Place

Surely the prettiest street in Fitzrovia? I couldn’t resist this setting for the final chapter of Liberty’s Fire, although you have to imagine it without the window boxes and birdsong. Not wishing to give too much away about my book’s ending, A wide, quiet empty pavement and refreshingly flowery backdrop gave us a moment away from passing traffic and pedestrians to discuss why London was such a magnet for revolutionary exiles, and how we know about what they got up to when they got here.

London was an obvious destination for escaping communards: its size and publishing industry offered the best chance of work, not to mention political sympathy and French speakers. Within the capital, Fitzrovia had plenty of cheap accommodation, and was already well established as a home of freethinkers. Cleveland Hall, for example, was a centre of secularism, where Harriet Law, the first woman in the First International and a salaried public speaker had been lecturing since the 1860s.

Patriotic libertarianism was a defining characteristic of Victorian Britain, a nation which utterly refused to kow-tow to despotic foreign governments. This made it one of the few countries in Europe where you couldn’t be extradited for political crimes. Communard, journalist and novelist Jules Vallès (another great source for Liberty’s Fire) was deeply critical of London, not least the lack of places the city offered for illicit sex, and the canoodling on park benches that resulted, but said London taught him ‘what Liberty is.’ Kropotkin became cynical about the joys of free speech, press and assembly, arguing to Emma Goldman that political liberties here were actually the best security against the spread of discontent: ‘The average Britisher loves to think he is free; it helps him to forget his misery. That is the irony and pathos of the English working class.’

And the most fruitful source for academics researching French exiles in London? The police records. Spies and informers flocked to Fitzrovia too, and anonymous agent reports found their way back to Paris. You couldn’t step out onto Charlotte Street without bumping into a ‘mouchard’. Not that their reports were necessarily reliable. Denunciations and counter-claims were frequent. (Nick Heath paints a lively picture of the espionage scene here.)

Charles Malato’s satirical memoir of his time in the ‘small anarchist republic’, The Joys of Exile, (Les Joyeusetés de l’Exil)is extremely entertaining but also needs to be read with a small pinch of salt. I would dearly love to find out more about Malato, a fascinating character who was exiled to New Caledonia with his father in his teens and ended up in London as a journalist, Henry Rochefort’s secretary, and also the French correspondent for Freedom, who provides very lively descriptions of our next characters, and was also the author of a vaudeville play staged at the Autonomie Club called ‘Dynamite Wedding’, which mocked clueless spies and Parisian police agents. The final chapter of his book, a guide to new exiles, includes a hilarious phrasebook, giving first the French, then the written English, then 'Anglais parlé' in a heavy French accent, with useful expressions like Bladé forégneur!, Oh! maille pôr belli and Ite iz improper you nême de mêlée of de henna, ouse nême iz olso given tou enne odeur tin'gue ('It is improper to name the male of the hen, whose name is also given to an other thing.')

Fifth stop…via Goodge Street…59 and 67 Charlotte Street

![]() |

| 67 Charlotte Street |

![]() |

| 59 Charlotte Street |

As we left Conville Place, I had to announce an on-the-hoof change of plan…a hasty discussion with Linus of the Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre about changes in street names – presumably the bane of all city guides’ lives – had just revealed that our next stop was not where we thought it was. The Librairie Internationale, the bookshop and newsagentrun by Armand Lapie, and probably the most heavily policed and spied-upon spot in Fitzrovia in the 1890s was not at 30 Goodge Street but at 30 Little Goodge Street – now renamed Goodge Place, and precisely where we had begun our walk. Actually, a much more atmospheric spot too – the street bends nicely, so you can imagine people hiding round corners – and it's one that’s changed less since then than many. I’ve not yet been able to establish the numbering in the 1890s, so I’m still working on the precise location of the shop, which was a crucial crossnational hub for continental anarchists, while Lapie has been revealed as by far the most densely connected individual in those circles. Later, in Geneva, Lapie later published the memoirs of Victorine B. – Souvenir d’une morte vivante– another of my key sources. Madam Brocher – as I later discovered – was also involved in Michel’s school. More and more links kept emerging….

So we hurried back to Charlotte Street, where Louise Michel lived at one point, at no. 59. She had quite a few London addresses over the years, including one just round the corner from where I live now in South London, and seems to have shared most of them with one or more cats…she even came back from New Caledonia with several stray felines in her pockets, and was as incapable of passing an animal in distress as she was of walking by a suffering human being. (Did you notice the cat - and the policeman - in the picture of the Newman Passage co-operative kitchen?)

A few doors up was another landmark to which newcomers were always directed, Victor Richard’s épicerie. Malato paints the grocer in Rabelaisian terms – rotund in figure and character, bald, pink and charming – and joked that he’d been radicalised by prolonged contact with red beans and believed white ones to be reactionary. He also said that before his flight to England, Richard had contributed to the defeat of the Prussians by supplying the French army with beans that made them fart and that he advocated pickling the deputies of the Versailles government and feeding them to the hungry of Paris. A great friend of Vallès, for years Richard provided exiles with a poste restante and staging post.

Sixth stop: 19 Fitzroy Street

And finally we came to the site of the International School where educationalist Margaret McMillan - named as a teacher on the prospectus - was shocked to find children gazing at pictures of Communards lined up against the wall to be shot and the hanged Haymarket anarchists of Chicago. I had been confused about exactly where the school was, as so many accounts put it in Fitzroy Square - where a suitable corner building still stands - and my hopes were further raised by finding a painting in the Tate of that building by Henry Nevinson’s son Christopher (think Kit Neville in Pat Barker’s Life Class). But Fitzroy Square was actually the name given to the whole area in those days – ‘Fitzrovia’ wasn’t coined until the 1940s – and both the prospectus itself, and the two leading historians of the school, Constance Bantman and Martyn Everett, confirmed that the school really was in Fitzroy Street.

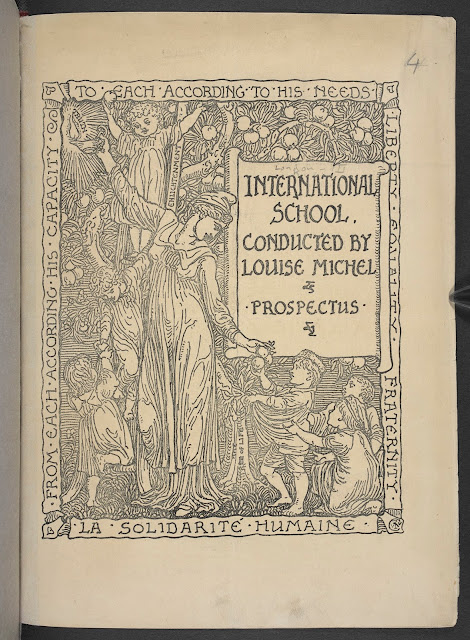

The school itself definitely deserves a blogpost of its own, on which I will hold off until Everett publishes his research later this year. All will then become clear, I hope, about the role played by Michel's colleague and school secretary, agent provocateur Auguste Coulon, the 'vile' spymaster Melville, and the bomb-making equipment found in the basement that seems to have got the school closed down. Today I will leave you to admire the beautiful cover of the school's 1890 prospectus designed by no other than Walter Crane. I first encountered Crane on my mother's knee at the piano, and introduced him to my own children the same way, singing nursery rhymes like 'Lavender's Blue' from the exquisitely illustrated pages of The Baby's Opera and The Baby's Bouquet. Of course my mother, my grandmother and my great-grandmother must all have sung from those pages too. I didn't even think about his politics.

![]() |

| ©The British Library |

I love the fact that this teacher plucks apples for her pupils from the Tree of Enlightenment rather than the Tree of Knowledge. She wears a liberty cap while filling her lamp with the oil of Truth. No surprise, looking at this, to find the name W. Morris among the Honorary Members of the school's committee. 'From each according to his capacity, to each according to his needs', a slogan popularised by Marx, was actually first used by the French socialist Louis Blanc - not a Communard, but in the provisional government set up after the 1848 revolution - who lived in exile in London (though in St John's Wood rather than Fitzrovia) until the Third Republic was declared in September 1870 when he rushed back to Paris.

Turn the page, and the prospectus announces its principles to be those of Mikhail Bakunin, founder of collectivist anarchism, who believed 'the whole education of children must be founded on the scientific development of reason, not on that of faith; on the development of personal dignity and independence, not on that of piety and obedience. . . the final object of education necessarily being the formation of free men full of respect and love for the liberty of others.' Louise Michel naturally does not forget her girls, and adds beneath: 'In a word, therefore, the object of the School is to make free and noble-minded men and women, not commercial machines.'

Tramping the streets looking for clues while you're researching a historical novel is a wonderful thing…tramping them after you've written it, in the company of curious and like-minded strangers and new acquaintances, even more so. Long may the Fitzrovia Festival and the Neighbourhood Centre continue to flourish.

www.lydiasyson.com

.jpg)

_-001.jpg)