![]() |

| Photo Credit: Mary Cregan |

We are delighted to welcome James Shapiro to the History Girls as our October guest.James Shapiro, who teaches English at Columbia University in New York, is author of several books, including

1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (winner of the BBC4 Samuel Johnson Prize in 2006), as well as

Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? He also serves on the Board of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear is published by Faber and out now. Find out more at

www.jamesshapiro.netMary Hoffman: Thank you so much for agreeing to appear on our blog. We know how busy you must be with your new book 1606 out this month and your academic teaching.

Confession time: you are being interviewed by a fan, who has read

1599,

Contested Will and now the new book. Like you, as you said in your YouTube interview about

1606, I never tire of thinking about Shakespeare’s work.

OK, on to the questions: First 1599 and now 1606; what do you think it was about those two years, one Elizabethan and one Jacobean that turned them into such fruitful periods for Shakespeare?

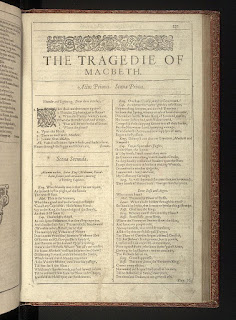

James Shapiro: The great challenge for Shakespeare in 1599 was writing plays that would draw Londoners to the Globe his company’s newly erected theatre in Southwark, rather than to the plays of their rivals, the Admiral’s Men, who were well established at the adjacent Rose Theatre. The pressure to write a string of box office successes, culminating in

Hamlet, must have been intense. 1606 turned out to be a great year for Shakespeare—one in which he wrote three remarkable tragedies—in large part because it was such an awful year in England: he made much in the plays he wrote this year of the tumult of the times. Shakespeare seems to have written plays in inspired bunches—though the sources of inspiration, and the pressure to produce, necessarily changed over time, as they do for all writers.

![]() |

| The new Globe on Bankside |

MH: You’ve said that you hated Shakespeare as a kid and didn’t acquire your addiction until you were a young man visiting London and saw the plays performed. Have you encountered any of Shakespeare’s plays first on the page or did it take seeing them to bring understanding and enjoyment?

JS: Shakespeare wrote his plays to be performed, not read; so I’ll take Shakespeare onstage rather than on the page any day. I reread and teach the plays every year but it is only when I see them staged, or work with acting companies in rehearsal (something I am doing more and more these days), that I really get excited or discover new things in them.

MH: I watched your BBC4 series “The King and the Playwright” about Shakespeare as one of James the First’s King’s Men acting company. Did

1606 grow out of your research on that?

JS: I’m glad that you had a chance to see it. After finishing

1599 on the Elizabethan Shakespeare I realized how little I knew about the Jacobean one who wrote plays—including some of his greatest tragedies and romances--from 1606 to 1613. So I was very lucky to be asked to co-author and present that 3-hour BBC series. It forced me to learn a great deal in a brief time period—and do so in a vivid way and imagine the period visually. There was a lot to learn. So, yes,

1606 definitely grew out of the research for that documentary and is a much better book because of that.

MH: Your chapters on Lear made me look at the play afresh, even though I’ve known it since it was a set text for my English Literature ‘A” Level exam. Stupidly, I had never made the connection between Lear’s dividing of the kingdom and James’s pressing for Union. Can you outline that argument briefly?

![]() |

| Lear and Cordelia by William Blake |

JS: The play famously begins with a discussion of Lear’s “division of the kingdoms.” Everyone in the playhouse in 1606 would have heard echoes of what was going on at this moment outside the Globe: King James’s plan to unite his kingdoms into a Great Britain. Should the kingdoms unite or remain divided? James, as King of Scotland and now England (and by extension Ireland and Wales and even France), complained that he would be a bigamist were he married to more than one nation. His efforts to create the Union this year failed. He would create an identity crisis where none had existed before, one that Shakespeare was quick to exploit, turning in his plays from questions of Englishness to those of Britishness. The fault lines that threaten to divide Scotland and England today can be traced back to the bitter debates over Union in 1606, and which powerfully inform

King Lear.MH: You set the three plays,

King Lear,

Macbeth and

Antony & Cleopatra, in the political and social context of that year: the influence of debates on Union, the aftermath of the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, the plague and the visit of Queen Anne’s brother Christian of Denmark to London. It all makes perfect sense. Why do you think no one has taken quite this approach before?

JS: Many, many scholars have drawn attention to the ways in which these plays respond to their times, and my long bibliographical essay at the end of my book acknowledges my debt to them. But they tend to do so in studies or editions devoted to one of the plays or have done so in scholarly articles or books that aren’t intended for broader audiences. Academics aren’t rewarded for writing popular books or for taking more than a few years to complete a monograph. I’ve drawn on a lot of scholarship, added to it some of my own, and, as with

1599, tried to frame it within a more gripping narrative, tried hard, as well, to bring that moment to life, using the plays to illuminate the times, and the times to illuminate the plays.

MH: You’ve been a Sam Wanamaker Fellow at the Globe in London and have clearly been involved in the new indoor theatre there. How closely do you think it replicates seeing Shakespeare performed in the indoor theatre at Blackfriars where the later plays were staged and perhaps written for? (though later than 1606 of course).

JS: As plague raged in late 1606—and threatened the survival of the boys’ playing companies, including the one renting the indoor Blackfriars Theatre—Shakespeare knew that it would only be a matter of time before he and his fellow players would acquire Blackfriars (they were already in negotiations for it). I love the indoor Wanamaker stage at the Globe thetre, and am thrilled whenever I get to stand on the stage there (though always worry about banging into the candles when I do). It’s probably the closest we will ever get to recreating the experience of Blackfriars, and seeing productions of Jacobean plays like

The Duchess of Malfi in that space has been thrilling. I can’t wait to see Pericles there next month.

(NB: I wrote about

the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse here last year. MH)

MH: From the hideous executions of the Gunpowder Plotters in January to Lancelot Andrewes’ Christmas sermon “of warning and consolation” 1606 was a dark year. Is this the reason ultimately that all three of the great tragedies written in that period end so bleakly? Even with Malcolm taking the throne in the Scottish play we know his line will be overthrown by Banquo’s heirs.

JS: It certainly was a grim and divisive year. I agree that the three plays he wrote this year all end tragically, though I would say that the endings are not dark in quite the same ways. The ending of

Lear is certainly unrelievedly grim, with the deaths of Lear and his three daughters (all the more grim when we remember that in his source play, King Leir, the king survives and is reconciled with his youngest daughter).

Macbeth ends more hopefully, if equivocally; as you rightly note, we are left wondering why Malcolm and not Banquo’s heirs, are in power at play’s end.

Antony and Cleopatra ends on a surprisingly different tragic note: yes, the two title characters commit suicide, but there is something defiant and even nostalgic in Shakespeare’s portrayal of their ends.

MH: Most of the members of this blog write historical fiction, covering many different periods. Hesitantly I ask if you ever read books in that genre and whether you have ever found fiction or narrative non-fiction illuminating in your study of Shakespeare? (I’m thinking of books like Jude Morgan’s

The Secret Life of William Shakespeare)JS: I’m friends with quite a few writers of historical fiction (I’m thinking especially of Grace Tiffany, author of

The Turquoise Ring and Andrea Chapin, who recently published

The Tutor). I enjoy their books and hugely admire their gifts. But it is very important for me to draw a line (one that they can cross and I cannot) between fact and fiction. Given the scarcity of facts about Shakespeare’s life, especially during the so-called “Lost Years’ of his early adulthood, it is a boundary that many scholars all too often ignore. So what I mostly feel about historical fiction is jealousy.

MH: Finally, can we expect a

1611? I’d love to read that.

JS:1599 took me fifteen years to research and write,

1606 another decade. I’ll have some challenging decisions to make about what’s next. I’m not sure that I have many more books (given how long these ‘years’ take to research) in me. But if I undertake another about another slice of Shakespeare’s life, 1610-11, in which he wrote

The Winter’s Tale,

Cymbeline, and

The Tempest would definitely be it.

MH: I hoped you'd say that! I have a sort of PS for you: I had always taken the Fool’s metaphorical egg in King Lear to be a boiled one, not raw, because of eating the “meat” or yolk. But your analogy with the jagged edges of the shell resembling crowns has got me thinking. Thank you!

JS: You are very welcome—these were terrific and engaging questions. I hope that I have done justice to them. (And am glad you like the image of the broken egg with the pair of jagged crowns)

MH: You certainly have! Thanks so much for being our October guest. And readers look out for the competition to win

1606 on 31st.